God bless you, Mr Zizek. We forgive you for being too attached to the ‘90s

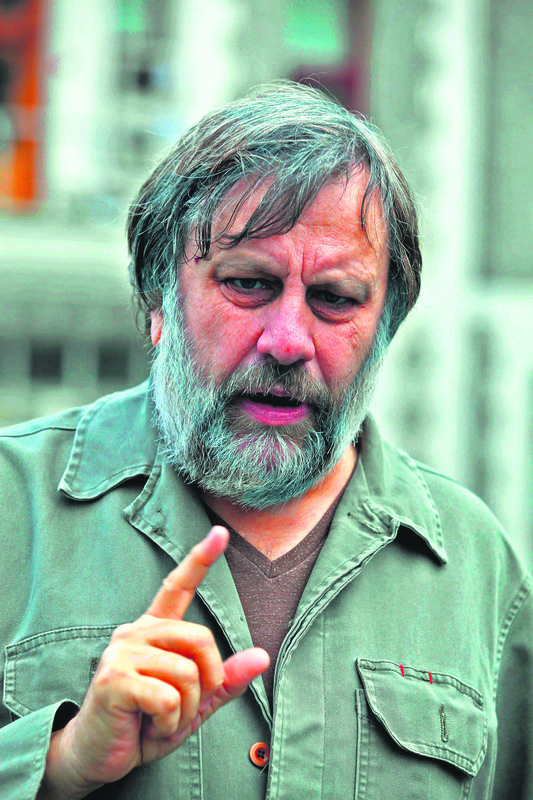

Criticisms voiced by Slavoj Zizek against the Turkish state are out-of-date, considering the significant progress made in the last decade. While he is a respected scholar, he seems oblivious to what is truly going on in Turkey

It was 2007, and as an undergraduate student I had the opportunity to listen to Slavoj Zizek at Istanbul Bilgi University. The conference room was packed and I could only listen to him from a live feed broadcast in another room. Zizek was warmly welcomed by members of the intelligentsia in Turkey. His critique of neoliberalism and capitalism had contributed to my understanding of the modern world and meant a lot to me. Yet two days ago when I saw a tweet that announced: "Zizek, wrote for Cumhuriyet " I was surprised, although my surprise did not last long because the article was originally published on the website of the NewStatesmen. What struck me was how Zizek's unconditional support for two journalists from Cumhuriyet daily had transformed into him writing for the very same journal, becoming the willing tool of the paper's anti-government stance and propaganda. In the past few years, Zizek's positive public image has come under serious pressure after he succumbed to a kind of European political correctness – as his critics always scolded him for – on his evaluations of the issues of migration and the ongoing crises across the Middle East, in what many would call a naive and discontented manner full of Central European bias.Speaking from the luxury of being able to freely move across the borders of privileged Europe, Zizek pontificates about Turkey, blaming it for DAESH fighters crossing into Syria. Conveniently, he neglects to note that Turkey had allowed free passage across its 900-kilometer border with Syria for humanitarian reasons.His accusations that Turkey facilitates the purchase of DAESH oil fall flat when one considers that several nations closely monitor the border crossings. DAESH continues to generate high revenue from the rich oilfields it controls in Syria, Iraq and Libya and it is the brokers and buyers from the so-called civilized world of Zizek that allow this to happen.Nonetheless, it is somewhat astonishing to hear such clichés from an individual who was previously seen as a strong, honest and certainly direct critic of these standards and stereotypes, who now says: Turkey was not only discreetly helping DAESH by treating its wounded soldiers, and facilitating the oil exports from the territories held by DAESH, but also by brutally attacking the Kurdish forces, the ONLY local forces engaged in a serious battle with DAESH. Plus Turkey even shot down a Russian fighter attacking DAESH positions in Syria.I do not know when or why Zizek turned from a bold critic of Russian aggression to a sympathizer of these very same kinds of deeds and actions. It begs the question whether Zizek's friends in Turkey are misdirecting him. How can he regurgitate this old-fashioned criticism of state-terror, which were valid in the 1990s but are no longer? How could he now be a part of, or even orchestrate, consciously or unconsciously, a very well-coordinated campaign against President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, a campaign that was originally launched by Gülenist or PKK sympathizers. Such blatant misinformation that forms the basis of Zizek's arguments, which present a very false image of Turkey, has become a staple of Western media, and its constituent parts should be tackled individually.Out of date, out of touchThere is no doubt that Turkey was a more closed country until the early 2000s. Efforts to achieve a high level of literacy, which was one of the top objectives of the Republic of Turkey, failed, with Turkey's literacy rate was still much lower than similar countries until recently. The state's exclusivist policies prevented its mass education programs, which are free, from reaching remote areas and disenfranchised groups.A homogenous and secular doctrine created a Turkish identity aimed to impose a half Sunni, though not pious, citizen to the nation. Alevis, pious Sunnis and Kurds had no place in this new order, nor did they deserve to fully benefit from the public services offered and their appearance in public was discouraged.Zizek's analysis of the Turkish state is very true and his criticism is accurate, but mistimed by a few decades. Since its beginning, the Turkish state presented an overarching force that defined, designed and redesigned what it meant to be a citizen.Kurdish identity, for example, was the victim of the unquestionable enforcement of state ideology. Indeed, the Kurdish question and the challenge to resolve it emerged from the state's attempts to impose overwhelming Turkish homogeneity on Kurdish language, identity and culture.Once resorting to armed violence, both the PKK and its now imprisoned leader, Abdullah Öcalan, virtually had the full intellectual and resourceful backing of the Kurdish people living in southeastern Turkey. The state's response was military only and mostly based on a strategy to end the struggle at all costs, resulting in countless deaths, internal migration, forced replacement and evacuation of settlements, not to mention socio-economic deterioration in the region and impoverishment, even among Turks. The Kurdish question, under the heel of the military and through the supervision of high-rank, retired military officers turned politicians, culminated in a low-intensity civil war between PKK terrorists and the Turkish military in 1990s. Kurdish integration cannot be airbrushed outThe Turkish state that Zizek recalls was a functioning interventionist "big brother" government. Zizek is certainly familiar with this story. However, the story he presents as truth lacks the developments of the past decade and the transformation of the relationship of the state, society and individual, which to me is astonishing.The Justice and Development Party (AK Party) opened a new chapter in state-society relations and initiated a new and comprehensive understanding of not only the Kurdish problem, but also all other, mostly identity-based, social issues, which the state repressed for decades.It was AK Party government first and foremost that initiated an introspective and self-critical analysis of the state. The new strategy was based on accepting identities, differences, striving for coexistence and finding a way to end the vicious cycle of bloodshed.The AK Party's stance was the natural outcome of its rise to power as a social movement rather than a political party, a grassroots outfit shaking the roots of the dysfunctional, century-old habits of the state in all senses.It was a grassroots response to the established elite, status quo supporters and bureaucracy-military alliance against elected politicians. In its second term in power, the AK Party government introduced a political angle to the Kurdish question, which had previously been the military's arena.The policy grew as a self-critique of the state and built up over time from a de facto policy of denial of Kurdish identity to affirmative behavior and acceptance of Kurdish demands, which I believe has been among the AK Party governments' brightest achievements.This was called not a peace process because every peace recalls war, not a solution process as many insist on referring to it, as a solution is for a problem, but Kurds are not a problem, it was a reconciliation process that required many reforms, reconciliations and amendments for the region and the people.A single example might suffice to explain the multi-legged and multi-layered process. My father's mother tongue, Kurdish, was banned for decades, even for daily conversations. Singing, writing and even whispering in Kurdish was deemed illegal. We still remember the comic yet tragic story of Musa Anter's whistling, which was punished because he was supposedly whistling in Kurdish. No one could claim Kurds were citizens as long as they could not speak their own language in public or benefit from state services, including hospitals, courts or schools, if they spoke Kurdish.We also remember all too well the oppression of private publishing and broadcasting. Turkey now has a state-run channel that broadcasts in Kurdish. No restrictions on the language remain. Even Öcalan's letter in Kurdish was read aloud in Diyarbakır during the Nevruz celebrations in 2013, which many saw as a turning point.This was the situation just before the June 7, 2015 general elections when the pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) secured 13 percent of the vote, which the PKK saw as a license to cancel the cease-fire with the state and take the fight to the cities.As it stands now, the state is fighting against a terrorist organization that is responsible for a range of crimes, including kidnapping, killing troops and police officers and bombing hospitals and schools. One key difference with the 1990s is that now the state is trying to protect its Kurdish citizens from PKK violence.In the southeast, militants dig ditches – with equipment owned by the state and with the tacit approval of mayors from the HDP's regional affiliate Democratic Regions Party (DBP) – kill human rights activists like Diyarbakır Bar Association Chairman Tahir Elçi, have burned a 16th century mosque and try to sabotage social cohesion while killing the hope for a lasting peace that Kurdish people need.The PKK is putting entire neighborhoods under siege, shooting Kurds who voice disapproval while hiding in homes behind innocent people. The state is determined to fight the terrorist threat, which it considers a national security problem. The HDP's insistence on siding with violence further enhances the social, political and economic difficulty the Kurds are pushed into. These are the facts as they currently stand. Zizek's point of styling the Turkish state as "rotten" is unfair. The state we have now can be better, but it is a significant improvement when compared to how it was in the 1990s.A friendly offerZizek would do well to do his research more thoroughly. How could such a gifted scholar fail to note that many groups in today's Turkey enjoy freedom, reconciliation or even compensation for past injustices? Socio-economic investments and cultural-social rights are now guaranteed for the Kurdish people.The government continues to initiate democratic reforms, offering further rights and freedoms to long-neglected Kurdish citizens.No one can deny that there is still much to do. The Turkish state is still huge and cumbersome with a gigantic bureaucracy. Better institutionalization, more democratization and introducing an improved culture of accountability is needed.Yet, as a country located in an extreme region, Turkey is still a functioning democracy – the only democracy in the region. Granted, Turkey is still not a haven of freedom of speech, although there is no limit to criticism one can publicly make in the press. This is huge progress compared to only 10 years ago.I wish Zizek would better evaluate all the other issues that he touches on as the signs of a decayed state– the Gezi Park protests and Cumhuriyet daily to mention just two – rather than parroting the biased and ill-informed ramblings of the Western media concerning these over-publicized events.Once Zizek realizes that his acquaintances in Istanbul, who most probably observe the country from the confines of Cihangir, misrepresent and distort what is really happening in Turkey, he is welcome to visit us at Daily Sabah for a more balanced and factual approach. Primary information is always better than secondary sources, after all.

Last Update: January 04, 2016 18:08