Numbers don't lie but lying with numbers is possible

Michael Rubin's deliberate miscalculations on the Nov. 1 elections and spreading them online only reveals his concealed intentions and political attitude toward Turkey, but is far from reflecting the reality

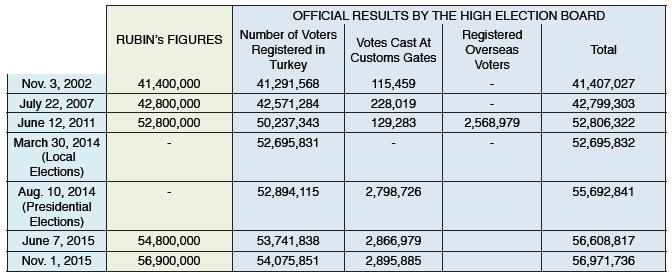

In the age of the Internet which allows us to "google" and confirm every piece of information, people of the "Big Data" society, who want to overcome worries about objectivity and disinformation, pay utmost attention to the language of numbers, thinking "numbers don't lie." But what if the wizards in the age of Big Data abuse numbers for their speculation despite the absolute honesty of numbers? In a piece dated Nov. 4 (See: http://www.aei.org/publication/the-numbers-prove-the-akp-cheated-in-turkeys-elections/), Michael Rubin gave a living example of creating an illusion through numbers. Making use of the technological benefits of the modern world, Rubin discloses electoral fraud, which was not noticed by national or international electoral observers, by using only his computer and the subtraction operation of mathematics. Rubin calculates the total number of voters for the June and November 2015 general elections, using different formulas and puts the increase in the number of voters during the five months at 2,100,000 instead of 300,000. With a calculation error that he describes as "plain and simple fraud," Rubin presents 1.8 million new voters to Turkey.During the transition from an industrial to an information society, the amount and types of data have increased at a mind-boggling rate that has tested the limits of the human mind. However, the processing capacity of the human mind hasn't seen a similar improvement. So, in order to construct his perception of the world, the modern man needs intermediaries that process data and make it ready for use. And those people who produce information to meet this need and have influence over the channels through which it is disseminated have come to enjoy such power as to define the normal of the new era and construct the world of the modern man. In the world of Big Data, this uneven power relation in the production and dissemination of information brings concerns over objectivity and disinformation to the forefront. As a consequence, those producers and consumers of information, who want to keep away from subjective reasoning based on misleading information and bring objectivity forward, pay greater attention to what the numbers say. On the other hand, the decisiveness of numbers over objectivity hastens people in the Google era to adopt the principle "numbers don't lie" as a maxim. THE MORE GOOGLE THE MORE LIESThe results of Turkey's general elections on Nov. 1 show that people of the Google society, who believe in the honesty of numbers, have been proved right once again. Quantitative analyses based on objective information, like the post-election survey conducted by Ipsos in the aftermath of the June 7 elections (See: http://www.cnnturk.com/turkiye/ipsostan-cnn-turke-secim-sonrasi-arastirmasi), which predicted the possible result of the Nov. 1 elections months in advance. In contrast to the discourse, wars and informational chaos in the media, the numbers did not lie despite the contrary wishes. But can we think of the same, in spite of the absolute honesty of numbers, for the wizards of pseudoscience who use numbers cold-heartedly? In other words, what if some people lie using numbers in the age of the Internet in which numbers don't lie? So, in a piece titled "The numbers prove the AKP cheated in Turkey's elections" and dated Nov. 4, Michael Rubin uses the language of numbers to demonstrate one of the most typical examples of illusions of pseudoscience. Rubin calculates the total number of voters for two separate elections within the same year, through two different formulas. Thus he goes beyond all election observation mechanisms known so far and claims that the Nov. 1 elections were rigged. Not indicating the source of the data on which he bases his claims, Rubin takes as a basis the number of registered voters in Turkey between 2002 and 2015 and swings his sword by delivering as definitive a judgment as mathematics. According to Rubin's figures, the number of registered voters in Turkey shows a normal increase of 2 million between June 2011 and June 2015. But his figures demonstrate that the number of voters in Turkey, which is expected to increase by half a million every year, has grown by over 2 million in five months, from June to November 2015. Thus Rubin manages to prove that there was some electoral fraud, despite contrary reports by domestic and international electoral observers, using his computer and the basic mathematical rule of subtraction. At the end of his piece, Rubin crowns his victory with the sentence, "Numbers don't lie. Erdoğan stole this election, plain and simple."A lengthy piece can be composed to discuss Rubin's concealed intentions and political attitude toward Turkey, where he manages to blend mathematics and technology in striking fashion. But bringing out a lengthy and discursive analysis and going against the principles cherished by the people in the Google era would reduce the expendability of the produced information. In that case, the best course would be to rely on the honesty of figures and try to understand Rubin's intention by looking at the numbers whose source was indicated.In his piece, Rubin compares the numbers of registered voters for the five elections between 2002 and 2015 that he chose. As can be seen from the table, the data for the 2002 and 2007 elections used by Rubin matches with the official figures announced by the Supreme Election Board (YSK). As it is understood, Rubin and the YSK obtain the number of total registered voters for these years by adding the number of voters registered in Turkey and the votes cast at customs gates.As for the figures for 2011, however, the YSK's documents also included registered overseas voters in addition to the votes cast at customs gates. Thus, the total number of registered voters for the 2011 elections is given as 52,806,322; with 2,568,979 of them overseas and 50,237,343 of them registered in Turkey. Rubin also gives approximately the same figure for 2011. It must be pointed out that, if Rubin had calculated the total number of voters for 2011 by adding the number of voters registered in Turkey with the votes cast at customs gates – like for 2002 and 2007 – he would have obtained the figure 50,336,626.2+2=5It's hard to tell if Rubin noticed that change in the official documents or if he used the data he found useful for his purposes. But a responsible analyst would be expected to compare the data he obtained for 2011 with those for the other elections held until 2015. Rubin would have had to find out why the number of voters in Turkey has not increased during the last three years, if he had contrasted the data for 2011 with those for the March 2014 local elections at when overseas voters did not a cast vote (total number of voters: 52,695,831) or with those for the August 2014 presidential elections (number of voters registered in Turkey: 52,894,115).At the end of this chain of coincidences, Rubin adopts a different type of calculation method for the June and November 2015 elections, for reasons unknown. And despite the fact that the YSK's official figures are only a click away. Though Rubin calculates the total number of voters for the June elections in the same way he does for the 2002 and 2007 elections, for the November elections he uses the method applied for 2011. In other words, while Rubin chooses the sum of registered voters in Turkey and overseas votes for the June 2015 elections, he uses the sum of registered voters in Turkey and registered overseas voters for the November 2015 elections. Eventually, the subtraction operation whose result changes depending on which figures you choose causes the increase in the total number of voters during the last five months to be obtained as 2,100,000 instead of 300,000. Consequently, Rubin's almost mathematically definitive judgment emerges victorious – despite the veracity of the figures – in a contest that compares apples and oranges.Unfortunately, given his relative power in the dissemination of information, Rubin's judgment may be probably viewed as correct in the future, in spite of his manifest error. Rubin has not realized the mistake and revised the piece yet. And in the era of Google, veracity is measured by high PageRank rather than by correct calculation. This means that; 10 years hence, people of the society of Big Data may find Rubin's piece at the top of search results and believe that the November 2015 elections were rigged. Fortunately, despite this epistemic twist of the Google era, numbers are honest as always and reveal Rubin's intention. Besides, in spite of a very high PageRank, they add this annotation to Rubin's flawed judgment: "Michael Rubin distorts the data on the total number of voters, plain and simple." *Ankara-based Writer

Last Update: December 01, 2015 13:55