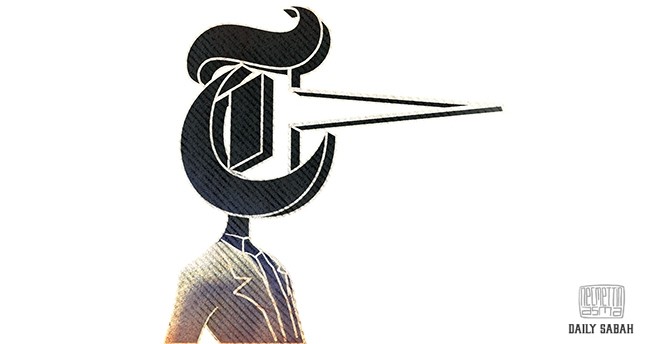

Is four weeks' suspension enough?

With repeated mistakes or biased attempts that were largely unexplained, it seems The New York Times' Twitter account needs to take leaf from its own social media policy and hence, take appropriate action as they did before when the perpetrator was a freelance journalist

Social media policy at The New York Times is a tad archaic and primitive compared to others in the business. Nevertheless, considering that it hasn't been updated for quite some time, it is still impressive as it manages to underline several basic principles.Let's look at an article, "After an Outburst on Twitter, The Times Reinforces Its Social Media Guidelines," written by Margaret Sullivan, the previous public editor at the NYT, on Oct. 17, 2012. According to the article, some workers at the Times weren't even aware of the guidelines:"Last week, I wrote about the insulting and profane Twitter messages by Andrew Goldman, a freelance writer at The Times, to the author Jennifer Weiner. At the end of that post, I suggested that it might be time for a clear social media policy at the Times.A number of staff reporters and editors later told me that there were such guidelines, but very general ones. Others seemed unaware that guidelines existed. And still others made the point that freelance writers, like Mr. Goldman, may not know that the Times' guidelines extend to them."Even though four years have passed since this article was published, looking at the social media accounts of reporters writing on Turkey, it is easy to see that some Times workers still have no idea about these guidelines. Of course, it could be that these reporters are aware of the guidelines but simply disregard them, which would be truly unfortunate.Goldman, the person mentioned in Ms. Sullivan's article, received four weeks suspension for his behavior while using his social media accounts even though he was a freelance journalist.Times magazine editor Hugo Lindgren said: "In light of his recent comments on Twitter, Andrew will not be contributing the Talk column to the Magazine for four weeks, beginning Oct. 28. He'll be back with the column after that" in a statement sent to Sullivan by the Times corporate communication office according to Sullivan's same article. Mr. Andrew was let go a year after this event for another reason but that does not relate to this week's subject.What does relate to our subject is the question: What if The New York Times itself violates the social media rules that are apparently firmly enforced once in a while even to freelance writers like Mr. Goldman? What if the official Twitter account of the newspaper features comments that are irrelevant, biased, hypocritical, factually wrong or include hate speech? What will be enforced in such cases to prevent further decline?Perhaps some examples are in order. Let us look at a tweet sent on July 19, three days after the failed coup attempt in Turkey by The New York Times World account:"The Erdogan supporters are sheep, and they will follow whatever he says."As the tweet itself was in quotation marks, one could think that this was a view given to the newspaper by a third party. But as we read the story, it was clear that it had no relevance to the story. After numerous complaints and criticism from social media, the following statement was sent:"The previous quote refers to an earlier version of this article. Here's our updated piece on the post-coup backlash."Two of the names credited to the article are Ceylan Yeginsu and Tim Arango. Even if you look past their biased journalism in this case, neither of these two names nor the newspaper itself apologized for their mistake. And that's not to mention the mystery of how a sentence that was written and then deleted could have been used when posting on Twitter.Another scandal arose revolving around these two names. Arango and Yeginsu used the word "invasion" when reporting on Turkey's operation against DAESH. Considering that the New York Times never dubbed United States operations in Syria against terrorism as "invasions," the double standard is clear as day. Once readers made their displeasure known, the headline was changed. Yeginsu said the following regarding the matter:"I have deleted an older version of this tweet, which contained an erroneous headline. Here is the correct version."This was supported by Arango who said "invasion" is not in the story. And headline was changed. Thank you."We too would like to thank Mr. Arango, but apparently he doesn't deserve it. It seems both Yeginsu and Arango either don't even read what they write or they are lying – because "invasion" was in the story. Let's take a look:"The invasion seemed to support the opinion of many experts that the Turkish military's combat capabilities had not been substantially diminished."Shortly after this fact was presented to them, they changed the word "invasion" to "incursion." Assuming that most readers have come across this word in a dictionary at least once or twice in their lifetime, it would not be stretching it to consider that such a "small" change would make no significant adjustment to the initial word "invasion." Yet, an apology or an explanation was unsurprisingly not forthcoming.Sullivan also mentioned the explanation of managing editor for standards, Philip B. Corbett, in her article mentioned here. Mr. Corbet said:"Anyone who deals with readers is expected to honor that principle, knowing that ultimately the readers are our employers."While this sounds good and well, it is clearly an imaginary employership. If the readers were really the employers, no doubt they wouldn't let the people responsible for repeated mistakes to continue working for them. Not for political reasons mind you, just because of their apparent incompetency.After being reminded of these mistakes, let us repeat the question: What will The New York Times do to correct such mistakes in their official account as they were so firm when dealing with even their freelance writers who did not follow the media policy? Would suspension for four weeks be enough? I do not think so. If they were determined to continue on this track, closing up shop would be more appropriate. After all, if it continues this way, Turkish readers surely won't buy their stories.

Last Update: August 29, 2016 01:26