© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

The projection shutters. Another pair of photographs appear, spliced side by side. Where a food shop specializing in foreign stock absent of all human presence ends, a lone man begins, fitting himself into a simple black leather shoe on the ground, surrounded by factory-issued merchandise off the sales floor. The old man wears a light grey, rounded, flat cap, something a shepherd might wear for shelter from the sun on a mountainous plain. He looks straight into the lens of the camera, flanked by shoes of all kinds. Rubber wellingtons stand in a neat row, while floral-printed slip-ons are stacked messily about heaps of bagged product, lined in boxes.

The effect, over countless varieties of twin shots photographed by Candida Höfer from 1972-1979, pictures the seamless visual continuity innate to Turks, in Turkey and in Germany. In her characteristically minimalist approach to titling her series throughout her very widely acclaimed career, Höfer presented these works as, "Turks in Turkey" and "Turks in Germany." Yet, despite her professional reach as a solo artist at such institutions as the Louvre, and in group exhibitions at MoMA, Guggenheim and many others of enviable prestige, the Dirimart exhibition "Times, Places and Spaces" is the first time in some 40 years that her early photographs have come to Turkey solely under her name, finally returned in top form to the country, culture and people whose faces and bodies, livelihoods and neighborhoods remain foundational to her creative life.

12 gelatin silver prints, sepia-toned, monochrome photographs line the spare, whitewashed walls at the Nişantaşı gallery, accompanying the ongoing, silent succession of projections. The prints are exclusively from her "Turks in Germany" series. There are certain dynamics at play that are apparent from both the human subjects of her photographs and her framing, particularly when her interiors are devoid of people. In all but one of her pieces with human presence, her camera is met with eyes that stare back, some candidly, others directly poised. Behind the scene, it is clear that, even in Germany, her series on Turks speak not only to the photograph in the frame, but also to the context of her shooting, where she is plainly an outsider. A picnic of four men and three children are affixed to her lens as she eternalizes them for "Volksgarten Köln III" (1974). Relatively unamused, they are not smiling as they sit hunched, looking back uncomfortably, as to wonder why they are the object of such fascination.

The curation of her 12 gelatin silver prints at Nişantaşı has the uncanny sense of distance closing in, an effect that comes with her outsider perspective as a phenomenon itself approaching her subjects with increasingly personal, intimate exchanges, before finally occupying the spaces in which they live and work. The series progresses as she advances toward the Turkish immigrant. "Volksgarten Köln II" (1974) is taken from at least a good 20 or more paces away, as she sets her photographic gaze on a quartet of covered ladies picnicking under a thick tree so tall that only its gnarly trunk is visible. One of the ladies seems in good spirits, though holding her arm awkwardly, looking at the camera with a faint smile. The others are merely perplexed.

What follows is the result of communication. A family portrait, "Volksgarten Köln I" (1974), is of laughter and joy amid a beautiful day outside, for Germans and Turks to meet, in Germany. And then, she takes a step back with "Rudolfplatz Köln I" (1975), entering male space at the mercy of not a few glares in a smoke-stained game room. The plaid suits, twisted mustaches and greased hair of the '70s jumps from the silvery surface of her vintage still.

A people to a place

In one of her earliest, purely interior photographs, eschewing the portrayal of people, titled "Handelstrasse Köln" (1975), Höfer captures the kitsch, ancient wallpaper of the day, onto which is tacked embroidered velvet murals glorifying the nostalgic, mosque-peaked cityscape of old Istanbul, only the ghostly visage of Atatürk rises in the sky like a full moon waxing the Turkish flag's crescent to fulfillment. From that conceptual departure, her works convey a literal abstraction from portraiture and documentation, towards a reflection of indoor space internalized by the artfulness of her meticulous framing.

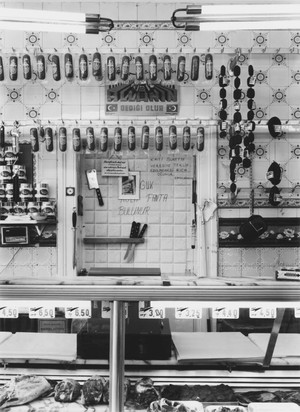

"Keupstrasse Köln III" (1979), as a late example in Nişantaşı evokes her maturity, not only in her photographic theory, but also of using her medium as a record of a specific time and place. She snapped a butcher shop, a cultural fixture for Turks anywhere, but the butcher is not present and neither are any customers. Though likely an interpretative stretch, the emptiness communicates postwar Germany's role in relationship to history and national space and to the global migrant crisis, considering the persistent legacy of Nazism, which continues to threaten the existence of minorities in Europe and abroad.

In the proceeding era of her creative momentum, after much of the arc of her career had rounded its lofty orbit between the years 2009 and 2017, she immersed herself in interior photography with one of the keenest eyes in her field, honed after decades of practice by her unique approaches to technical precision as a maker of fine images. To prepare for her exhibition at Dirimart, the artist was present. The result is a reflection of mirrors, an exhibition of her photography curated like a space within one of her photographs. The design of the warehouse gallery in Dolapdere transformed. A visitor has the expansive feeling of walking into one of her images, and that, it turns out, is exactly her intent.

"My work on Turkish workers in Germany made me aware of the environment in which people live and how they form it and how they are formed by it. This exhibition, I think, shows the circle very well: Interest in change led me to the series on Turkish people, the importance of space and the built environment led me to public and semi-public spaces, and the forms and colors that make up this environment led me to the abstract series," Höfer wrote over email.

The photographer as artist

Höfer studied under the conceptual, photographic artist duo Bernd and Hilla Becher at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. She was a classmate with others who share her degree of notoriety, like Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth, Axel Hütte and Thomas Ruff. They would help each other with technical issues. By then, she had already begun work on her Turks in Germany series. She describes the Bechers as atypical teachers. She remembers how they instructed with a non-directive style, emphasizing the environment, despite the subject.

Her interiors were shot in such opulent locales as the Neues Museum Berlin, Palacio del Congreso Nacional in Buenos Aires, Villa Massimo Roma, La Bibliothèque de I'INHA in Paris and the Catherine Palace Pushkin in St. Petersburg, among other vibrant pearls of world architectural accomplishment. In her hands, they unfold as from the hard shell of an oyster into a distillation of unearthly form. The colors alone are enough to demand awe. Yet, her manner of composition is equally mystifying, as she summons something of an immortal symmetry, like a Tibetan tangka, an Egyptian pyramid. She opens visual doorways through which viewers may experience the profound harmony of eternal architectural tradition and its worldwide flourishing.

She works simply. For her Turkish series, she used a hand camera. And for the interiors, she employed a digital back atop her camera. As for light, she assumes what is available, whether it is natural or artificial. A ceiling lamp is fair game. She does not prepare installations. When she began in the 1970s, she started photographing by hand, and then later moved to larger cameras. But recently, she has returned to her hand camera. In a small, dedicated room in the back of Dolapdere, her newest series of abstract photographs is inspired by Istanbul. Again, she roamed about its streets. Through her lens, a crumbling, Ottoman fountain takes its place in the history of abstract photography. The overcast skies of the city and a multicolored glass-paned doorway become absorbed in the visualization of human expression freed from the objectifying and overexploited sense of sight.

For all of her groundbreaking conceptual artistry and high institutional affiliation, both in her creative process and in her professional networks, she shies away from questioning whether photography is, as a matter of fact, art. "Photography looks like art, but art has to have some kind of depth," said Turkey's preeminent 20th century photographer, the late Ara Güler who passed away in October, during an interview with The New York Times in 1997. "Photography," Höfer wrote in response, "is just the best, and I am afraid only, way for me to make images."