© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

A bibliophile can learn a great deal from a bookshop in a country to which they are not a native. For example, to a British person like myself, a Turkish bookshop is especially revealing in its listing of numerous Turkish authors, some of whom I am already familiar with and others whom I am not. It whets one’s interest to find out more. Yet, it may also provide the additional blessing of revealing previously unknown foreign writers who have been translated into Turkish, having found greater appreciation in Türkiye than in the English-speaking world. Indeed, it was through their translation into Turkish that I originally learned of Mesa Selimovic, Cesare Pavese, and, in particular, the Austrian Jewish writer Stefan Zweig (1881-1942). Indeed, though works of Zweig do exist in English – indeed I will be drawing on a couple of them below, namely "Journeys" and "The World of Yesterday" – and his star has been rising in the English-speaking world recently, I feel that without his popularity in Türkiye, I would not have got to hear of him. I am, therefore, truly thankful for my introduction to him through Turkish, for I have now long ranked this highly sensitive and conscientious writer as one of the greatest and most important that I have ever read.

Among Zweig’s voluminous writings are travel essays. One of these is on the town of Ypres, known officially today by its Flemish spelling of Ieper, in Belgium, which Zweig visited in 1928. This essay has been of particular interest to me, as I recently completed a visit to the same place, almost a century after he did. The essay made me want to illustrate how Zweig perceived Ypres and how it has changed over the last hundred years or so.

There may be readers who are unfamiliar with the name Ypres. It is one of those places whose fame largely depends on a horrific aspect of its history. The names of these places, which would otherwise be relatively unknown, still toll out dolefully across the world: Auschwitz, Hiroshima, Mai Ly, and Srebrenica. Moreover, they do not all belong to the past. For there surely can be few today who do not know of Gaza. However, were it not for the horrors that are daily being committed there as the summation of its tragic history since 1947, it is unlikely that few but local people, Middle East experts or Bible scholars would ever have heard of it.

Ypres is a town that may be unfamiliar to those outside Great Britain and the countries that then comprised its empire in the 1910s, including Canada, Ireland, India, and others. For those from Britain and these other countries, though, Ypres can be imbued with some of the heaviness of the place names above. It was around the town of Ypres that, in World War I, the Allies, notably the British Army, fought four particularly bloody battles against the German Army in 1914, 1915, 1917 and 1918.

As such, Ypres draws visitors from Britain and its former empire. But Zweig was a citizen of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which was allied to Germany as one of the Central Powers. It may therefore be surmised that his reason for visiting Ypres was to mourn those who fell in the war fighting for this alliance. This surmise would be wrong, though.

For Zweig felt himself to be a European. He held the “conviction of the necessity for a unified Europe” long before such an opinion became fashionable on the continent. He was a European in this way before the war, after the war and most admirably remained one during the war. He declares that at the outbreak of war, “I had lived a politically cosmopolitan life too long to change all of a sudden ... to hating a world that was as much mine as my native country.” He therefore regarded World War I as an “internecine” disaster and referred to it not as the Great War but as “the great crime.” As the continent is torn apart into two blocs, each one intent on vanquishing the other, Zweig feels torn apart as well. There is a similar response in Pierre Loti, who, as an ex-naval officer, is a proud son of France, when the Ottoman Empire, which he adored, enters the war on the side of the Central Powers.

Zweig declares that initially, “all I could do was withdraw into myself and keep quiet while everyone else persisted in a feverish state of turmoil.” Yet, he does not remain quiet; rather, he uses his pen to express his anti-war views and works in solidarity with artists from countries at war with his own. This is an extraordinarily courageous action to take for a man whose very reputation and income depend upon public popularity.

Thus, following the end of the war in 1918, and in the following decade when some international understanding had been restored, it is unsurprising that, for Zweig, especially, all who fell in World War I, regardless of their nationality, were victims to be mourned. Thus, when he visited Ypres in 1928, he saw it as the “ville martyre” (martyred town), a heart-rending symbol of a conflict that had destroyed millions of lives and the European culture of Zweig’s youth. Zweig is in Ypres to remember all the victims of this conflict.

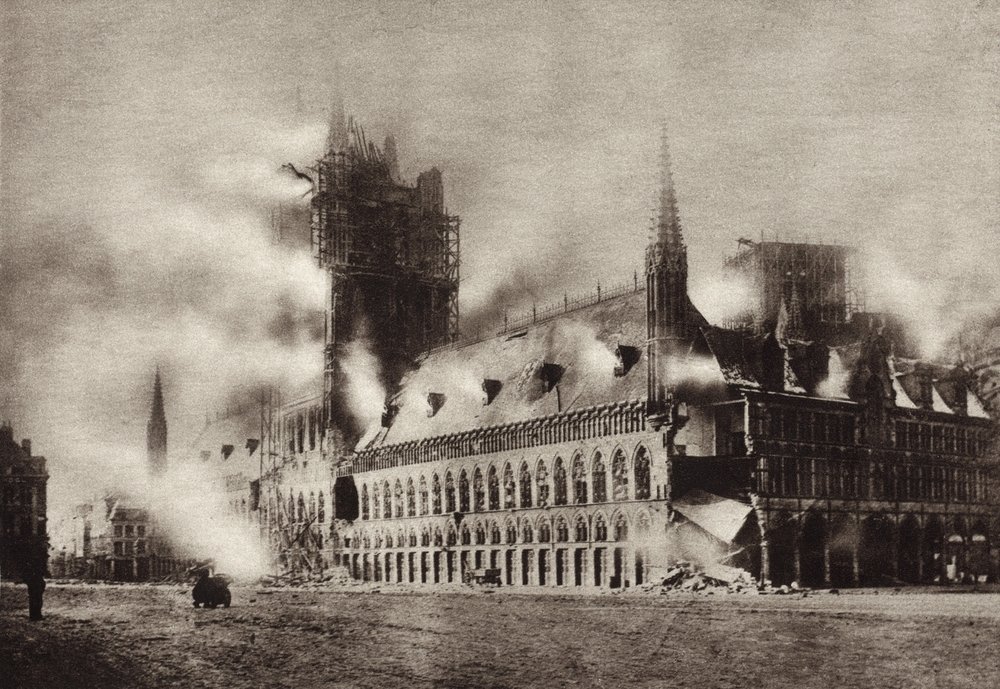

Interestingly, that visit by Zweig to Ypres was not his first. He had seen Ypres before World War I, drawn by its medieval Cloth Hall. Yet this building, for all its architectural splendour, had at that time hardly made the town into a tourist hot spot, Zweig calling the whole area a “slow and forgotten provincial backwater.” However, the situation was very different when he returned in 1928. Zweig notes that the town is now “Belgium’s star attraction,” revealing that, daily, at least 10,000 tourists visit the town.

For his postwar visit, Zweig must have chosen a similar time of the year to me, for although he approached the town from the north and I came to it from the south, I saw like him “to left and right, the undulating gold of ripening corn.” It is clear from Zweig that the arable land has been put back to use in the decade that has elapsed since the end of the war. Yet, nature had not by that time succeeded in fully recovering from the conflict, though Zweig is aware that it will do so, noting that “time erases the traces in the shifting earth almost as quickly as in the amnesic minds of men.” Nevertheless, at the time of Zweig’s visit, he could still write of “forests contaminated, their leafage yellowed by gas and eaten away, stretch their stumps towards you as if pleading for assistance.” A century later, though, the trees of Ypres and its environs look no different from those found anywhere else in the wider region. Indeed, while there are still traces of World War I in the ground around Ypres, during my visit, which lasted many hours, I saw none whatsoever.

Ypres does not appear to be the “star attraction” of Belgium anymore, overshadowed today by the capital, Brussels, and cities such as Bruges, Ghent, and Antwerp. Yet, over a century since the war came to an end, there are still visitors there – myself, of course and I saw a British coach tour stopped at the Essex Farm Cemetery, for instance.

Back in the 1920s, the wounds of the war were still raw and what would have particularly struck any visitor of sensitivity to the centre of the town in the 1920s was the state of the aforementioned Cloth Hall. This had been repeatedly shelled during the war and when Zweig saw it for the second time, it was as he puts it “a pile of rubble," it having been “decided that this unique building, the largest in Belgium at the outbreak of war, should remain for all time” in this way “so that generation after generation might remember.”

However, on my visit, the Cloth Hall was standing proud. Perhaps an expert on Medieval architecture might be aware that the current edifice is a restoration, but for the less-specialised eye, it would appear that the center point of Ypres has remained essentially as it was since the Middle Ages. Thus, there are no apparent signs of war damage in the town today. Indeed, I had not remembered that the Cloth Hall had been intentionally left in ruins till I reread Zweig following my trip. I have since learned that its restoration was begun in the 1930s, but I do not know why the original intention for it was set aside.

All in all, the visitor to Ypres of today is confronted by a restored nature and a restored town. Indeed, a century on from the visit of Zweig, I think it is true to say that it would be possible to visit Ypres, and take a walk in its surrounding countryside, and not be aware that anything historically unusual had ever occurred around the town. That is, but for two related elements of the city and its environs that are as striking today as in the time of Zweig. For he writes of “crosses, crosses and still more crosses, stone armies of crosses” as being an “overwhelming spectacle when one thinks that beneath each of these blank polished stones entwined by roses, lies a man.” And the cemeteries remain all around Ypres. Although I went in search of the Essex Farm Cemetery, which was marked on the map given to me by the tourist office located in the restored Cloth Hall, before I reached it, I came across the Duhallow A.D.S. Cemetery. Indeed, save for the Essex Farm Cemetery, none of the other cemeteries I saw were even marked on the map, which itself showed a large number. This gave me a horrifying indication of how many dead actually lay in Ypres.

There is a monument in the town that sheds some light on this dreadful number. And it was already there at the time of Zweig’s 1928 visit. It is the Menin Gate. Zweig is right to describe this imposing monumental marble arch to “fifty-six thousand British soldiers” as being “at first sight grandiose on an emotional level as much as an artistic one.” It is an enormous structure covered in etched names. Their regiments list them, and these lists, in their vastness, are overwhelming. And these are simply the names of those whose bodies were never identified or found, and only those from before the middle of August 1917, as there was not room on the monument for those additional losses up to the end of the war. So these names are not duplicates of those found in the cemeteries. And it must not be forgotten that the focus so far has been limited to the losses of the British Army. Tens of thousands of others also fell in Ypres, including, of course, German soldiers.

However, moving all of this still is, Ypres has a directness to a visitor of the 1920s that cannot be matched today. Speaking of the dead soldier interred in his grave, Zweig laments that but for the “madness” of the war, “that man would be forty or fifty today, full-blooded and in rude health.” Today, of course, even if these soldiers had survived the war, none of them could still be alive.

The mass tourism that engulfed Ypres in the 1920s also deeply disturbed Zweig. It revolts him that the people of Ypres “prosper by the dead” in that they serve this new influx of affluent foreigners, profiting off them with “curious made from shell splinters,” which, as Zweig painfully notes, “perhaps ... tore the entrails of a human being.” He also finds the nonchalance of the tourists themselves difficult to bear. He sees them treating a day at Ypres with easy transportation, fine dining and shopping, akin to a day’s holiday. Zweig deplores that these visitors “can, for on average ten marks, ponder at their ease, placidly, a cigarette to their lips, for a half hour or so, four years of martyrdom by half a million men, then conclude with a few dozen postcards that laud the experience as a sight worth seeing.” As such, Zweig is railing against what today is known as “war tourism.”

The reason that Zweig feels Ypres needs to be visited despite having to “mingle with this herd of amateur battlefield enthusiasts” is that he feels a “responsibility ... not to overlook any traces that bring to life in concrete terms the history of our epoch: For only in remaining so informed can we take on so terrifying a past and then be able to turn and face the future.” Thus this tasteless type of tourism is still good because “all that recalls the past in whatever form or intention leads the memory back toward those terrible years that must never be unlearned.” For Zweig, it prevents such a conflict from breaking out again in the future.

Zweig, though, would not be aware when he wrote this in 1928 of the irony that he was living in the last year of hard-won postwar stability. It was still possible then to believe that the war had been a “war to end war.” However, the Wall Street Crash of the following year would set off a chain of events that would lead, in 1939, to the outbreak of World War II, which would surpass World War I in terms of its horror and ultimately claim Zweig’s own life.

Following the cataclysm of 1939-45 and the numerous wars that have raged since, including those ongoing today, the visitor of today can no longer afford the naivety of thinking that learning from the past prevents its repetition. Indeed, they may even feel that focusing on past national traumas stokes feelings of resentment, making future wars even more likely.

If that is the case, though, then I have to ask myself why I was drawn to Ypres. Like Zweig, I feel cosmopolitan, I share his “hatred and abhorrence for war,” and do not think of myself as a “war tourist.” I also do not feel that battle sites meaningfully help visitors “understand” what the reality of war was like. I think that is even true in the raw state that still existed at Ypres at the time of Zweig’s visit, but all the more now that nature has fully recovered in the area.

Yet, I think my reason for visiting is not too dissimilar to that of Zweig, though it lacks his element of hope. As a child of the 20th century, I think that, in visiting Ypres, I too just wished to literally be present at a site that is highly significant in the “history of our epoch” and in this way to mark and be marked by it. Moreover, there was the simple desire to remember the great many young men cut down in early adulthood or even at the cusp of it, and the deeply humbling thought that had I been born two or three generations earlier, I could well have been one of them.