© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

The prevailing narrative of art history, polished in museums and repeated in textbooks, often paints creativity as the offspring of refined techniques, disciplined craftsmanship and stable mental composure. Yet the closer one scrutinizes the lives of artists who truly altered the trajectory of visual culture, the more this narrative collapses. Beneath the surface lies a far more complex and unsettling truth: The history of art is inseparable from the history of illness, not only as metaphor but as a biological, psychological and chemical reality. The ailing body, the destabilized psyche, the toxic studio and the traumatized social environment have all shaped artistic languages in ways that traditional art history has rarely acknowledged with sufficient seriousness.

This is not to romanticize suffering, a trap both popular culture and early psychoanalytic criticism often fell into, but to understand illness as a structural force that reconfigures perception, cognition and expressive capacity. Neurological studies also have emphasized that altered mental states do not merely disrupt creativity; they reshape the perceptual frameworks through which the artist experiences reality. In this sense, pathology becomes not an obstacle but a refractive lens.

Few figures embody this entanglement more dramatically than Caravaggio, whose life reads like a case study in unregulated neuropsychiatric deterioration. While art historians have long described his volatility as the temperament of a “violent genius,” recent interdisciplinary scholarship combining toxicology, medical anthropology and archival criminology paints a more nuanced picture. Caravaggio’s hypersensitivity to light, bouts of paranoid rage, insomnia, sudden collapses and alternating periods of manic productivity and profound exhaustion align strikingly with the symptomatology of neurosyphilis and lead poisoning. Many of the pigments he handled daily, ceruse (white lead), minium (red lead) and orpiment (arsenic sulfide), were known neurotoxins capable of inducing hallucinations, mood dysregulation and cognitive impairment. One might argue that his signature tenebrism, with its cavernous blacks and violently illuminated figures, echoes the perceptual constriction produced by both syphilitic optic inflammation and the cognitive hyperfocus associated with manic states. The “psychological chiaroscuro” of his compositions, therefore, becomes more than stylistic bravura. It reads as a phenomenological record of a man experiencing the world through a compromised nervous system. “David with the Head of Goliath,” in which Caravaggio uses his own face for the severed head, becomes not merely a dramatic gesture but a form of proto-expressionist self-diagnosis, a confession rendered in oil and fever.

Yet the medicalization of artistic vision is not confined to the Baroque. Francisco Goya, whose mysterious illness in 1793 left him deaf and intermittently delirious, underwent a psychological metamorphosis that no conventional biography fully captures. Modern neuro-historical interpretations suggest that Goya’s symptoms align with autoimmune neuropathy, possibly complicated by mercury exposure from cinnabar pigments. The hallucinations, social withdrawal and paranoia that followed were not incidental; they became the psychic fuel for the "Black Paintings," a body of work that feels excavated from the somatic depths of illness rather than consciously composed. In the absence of sound, his visual world grew unbearably loud.

J.M.W. Turner, in contrast, suffered not from mental illness but from a progressively deteriorating visual system. Ophthalmological studies suggest that his late canvases, once dismissed as the incoherent productions of an aging mind, reflect the perceptual distortions characteristic of cortical cataracts: blurring edges, diffused luminosity, heightened yellows and a collapse of linear clarity. Turner was, in effect, painting through the cloudy architecture of a diseased lens. And yet, these very distortions pushed Western art toward abstraction decades before abstraction had a name.

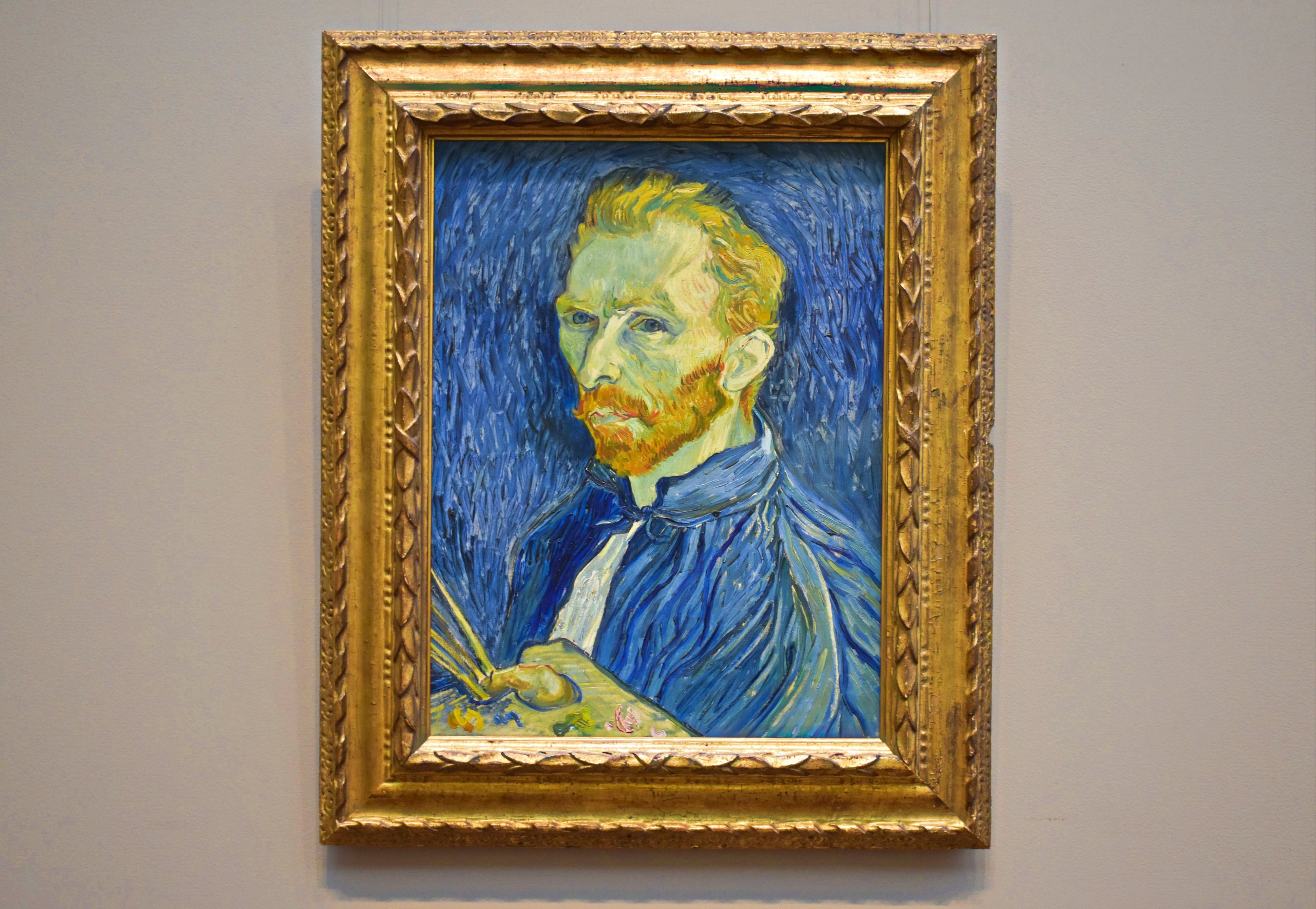

Vincent van Gogh, the eternal emblem of the “mad artist,” embodied a convergence of neurological fragility, environmental triggers and pigment toxicity. His symptoms, hallucinations, abrupt mood shifts, auditory distortions, hyperacusis and episodes of dissociation correspond to temporal-lobe epilepsy overlaid with bipolar disorder, amplified by the neurotoxic effects of lead white and thujone-rich absinthe. Neurologists note that the swirling patterns in “The Starry Night” mirror cortical discharge patterns seen in epileptic aura. Van Gogh’s paintings thus function as visual EEGs: not symbols of illness, but direct transcriptions of it.

While these narratives are widely discussed in Western art history, the Turkish and Ottoman artistic landscape contains equally revealing intersections of physiology, psychology and creativity, though these remain underexplored.

The painters of the Ottoman Nakkaşhane operated in conditions that today would be classified as hazardous: poorly ventilated rooms, airborne pigment particles and the prolonged use of toxic minerals such as verdigris, cinnabar, malachite and powdered gold. Ottoman archival records mention miniaturists suffering from chronic tremors, respiratory ailments and ocular strain conditions that modern occupational medicine would link to pigment toxicity and repetitive micro-movements. These physiological constraints shaped the distinctive stillness, precision and meditative equilibrium of Ottoman miniature art. Illness becomes an aesthetic engine, not an impediment.

Moving into the late Ottoman and early Republican period, psychological turbulence takes center stage. Osman Hamdi Bey, navigating the epistemic shock of modernity, produced works suffused with introspective tension. Though not clinically ill, he experienced what cultural psychologists might call “liminal identity fatigue,” a condition in which individuals straddling multiple cultural paradigms experience chronic cognitive load. His compositions, meticulous, restrained, introspectively melancholic, reflect a psyche negotiating the psychic toll of an empire crumbling beneath the weight of its own contradictions.

Far more overt is the case of Fikret Mualla, whose life reads like an annotated psychiatric textbook. Diagnosed with psychosis, burdened by alcoholism, cycling through manic expansions and depressive implosions, and institutionalized multiple times, Mualla transformed his psychological ruptures into a chromatic language uniquely his own. His Parisian street scenes vibrate with a frenetic yet fragile energy: distorted perspectives, electrified outlines and saturated colors that evoke hyperarousal states described in clinical psychology. His art embodies what psychiatry calls “the turbulent gift” – creativity arising not from stability but from continual psychic negotiation.

The Turkish canon also bears quieter tragedies. Hale Asaf, whose life was cut short by breast cancer, produced late self-portraits that radiate a soft despair – faces rendered with attenuated luminosity, forms dissolving into atmospheric vagueness. They mirror the psychological states described by psycho-oncologists: anticipatory grief, identity erosion and the existential contraction that accompanies terminal illness. Her art becomes a visual phenomenology of dying – subtle, unadorned and devastatingly lucid.

One must also note Abidin Dino, whose work produced during periods of political exile and chronic pain vibrates with what trauma psychologists term somatic memory. His elongated figures, often tense or distorted, echo the bodily imprint of displacement and persistent anxiety. Trauma is not represented; it is embodied.

When these global and Turkish narratives are placed side by side, a pattern becomes impossible to ignore: Illness, whether neurological, psychological, chemical or cultural, acts not as a deviation from artistic creation but as one of its most defining forces. As psychologists repeatedly emphasize, altered mental states recalibrate perception, heightening sensitivity to visual stimuli, collapsing conventional boundaries between inner and outer experience and compelling the artist to construct alternative visual grammars.

Thus, Caravaggio’s convulsive chiaroscuro, Goya’s deafened nightmares, Turner’s dissolving horizons, Van Gogh’s trembling skies, the Ottoman miniaturists’ meditative precision, Mualla’s manic distortions, Asaf’s fading luminosity and Dino’s traumatized bodies are not isolated idiosyncrasies. They form a global cartography of human fragility translated into visual form.

To study art without acknowledging the physiological and psychological conditions that shaped it is to sever the work from its origin. To recognize illness not as romantic suffering but as a structural agent of perception is to read art history anew with less mythology, more humanity, and a deeper understanding of the trembling hand that shaped civilization’s most enduring images.