© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

A salmon swimming upstream. This is how a family member describes Fahrelnissa Zeid, the wonderfully original Turkish artist whose works are on display this summer at Tate Modern. The Istanbul-born artist is best known for her large-scale abstract paintings and figurative works in her late career, but for her new, London audience, Zeid's fight against cliches and artistic convention are highlights of the artist's 70-year career.

Mixing Byzantine, Islamic and Persian influences with abstract forms, Zeid had established herself as an immensely original name in mid-20th century art history. "It is astonishing that an artist of such force and originality should have been practically forgotten, particularly in London and Paris where she was a prominent figure in the art scene for decades," says the show's curator Kerryn Greenberg.

Born into an elite Ottoman family in 1901, Zeid was among the first Turkish women to receive artistic training. Graduating from Istanbul's Faculty of Fine Arts, she traveled to Paris and studied at Academie Ranson.

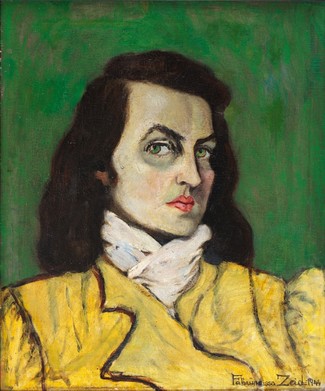

"Zeid began drawing and painting at an early age, inspired by her mother and her older brother, who dropped out of Oxford University to study art in Rome," writes Greenberg in the exhibition text. "The earliest work in this exhibition is a delicate portrait of the artist's grandmother, painted in 1915, when Zeid was 14 years old."

Zeid started exhibiting her works in the early 1940s. Those violent years of war, genocide and destruction found a counterforce in the world of art. During the war years in Istanbul, Zeid became part of the d Group, an avant-garde artistic movement. In 1945, Zeid opened her first exhibition in her apartment in Maçka. "Her subject matter at this time ranged from interior scenes and still lifes to nudes, portraits and landscapes," Greenberg writes. "Vibrant color and black line, which would become signature aspects of her later style, are evident in most of her works from this period."

"When I am painting, I am always aware of a kind of communion with all living things," Zeid had once said. "I mean with the universe as the sum total of the infinitely varied manifestations of being. I then cease to be myself in order to become part of an impersonal creative process that throws out these paintings much as an erupting volcano throws out rocks and lava."

The end of World War II changed Zeid's life dramatically, for it was during this time that her husband, Prince Zeid al-Hussein, was appointed Iraq's ambassador to the United Kingdom. From then on, Zeid would spend her life in the Iraqi embassy in London, where she ordered the building's maid's quarters to be transformed into a studio.

"As long as I had lived and worked in Turkey, I had seemed to distrust my own artistic initiatives," Zeid once said. "I was too isolated, too unsure of myself. Now I feel that I am at least understood and accepted, whether in London or in Paris, as an artist rather than as a kind of freak."

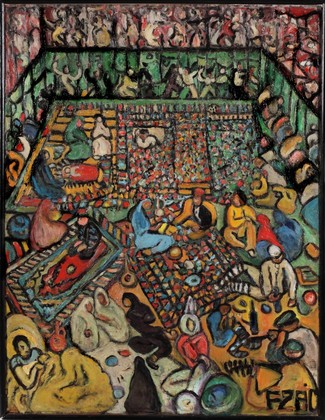

In London, Zeid moved in same social circles with diplomats, artists, and statesmen. When the Queen Mother Elizabeth visited Zeid's exhibition in 1948, she advised the Turkish artist to travel to Scotland. There Zeid came across a local festival in Loch Lomond, and was inspired by the scene. In her 1948 painting, "Loch Lomond" she combined the aesthetics of miniatures and abstract art. "In this painting, Zeid transforms bodies, tents and hills into a dense image dominated by lozenges and triangles," Greenberg writes. "While its composition and subject matter recall several earlier works painted in Istanbul, 'Loch Lomond' also demonstrates Zeid's growing interest in abstract references -- particularly the ways nature can be represented in miniature, fractal-like details."

It was a joy to come across "Beşiktaş, My Studio", an oil painting from 1943, at Tate Modern. Here the artist signed the work with a calligraphic signature in the Arabic alphabet. By the end of the decade, Zeid had forged herself a distinct artistic style. From the 1950s to mid-1960s, she divided her time between Paris and London, an extremely productive period when Zeid produced her large-scale abstract paintings.

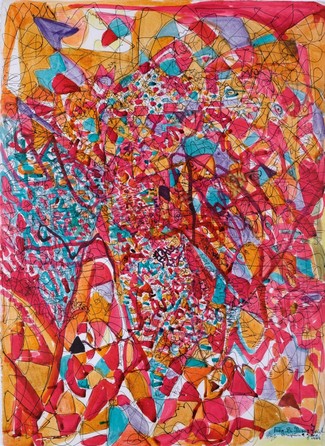

"These works reveal her synthesis of a wide range of influences, from nature and Islamic architecture to Byzantine mosaics and stained-glass windows," Greenberg explains. "Her determination and energy are evident in these crowded compositions, realized with rapid brushwork."

In the 1950s, Zeid started spending time on the Italian island Ischia, where she bought a holiday villa, and she continued with her artistic experiments. But the 1958 Iraqi coup d'état changed everything: the Iraqi royal family was assassinated, and Zeid and her husband were given one day to get all their belongings and leave the embassy in London.

Until her death in 1991, Zeid continued to be a mystery for art experts. Critic Denys Chevalier wondered in 1949: "What tendency, what group does Fahrelnissa Zeid belong to? What school do her works spring from?" According to Kerryn Greenberg, the Tate Modern exhibition cannot provide a single answer to that 70-year-old question: "The answers are complex and involve thinking across artistic, historical and geographical boundaries to reflect on how different influences fused and enriched each other in her work."