© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

The book “Segni di Diplomazia. Gli edifici della Rappresentanza Italiana in Turchia" ("Signs of Diplomacy. The Italian Embassy in Türkiye") grew out of a simple yet ambitious idea: to consider Italian architectural heritage not merely as a collection of buildings, but as a living archive of the long-standing relationships between Italy and Türkiye. This perspective was shared from the beginning, some years ago, by me, as an academic expert in the history of architecture, and my co-editor, Mario Magnarelli, an architect and restorer who was also professionally involved in the restoration of some of the buildings presented in the book, bringing direct, hands-on experience into the project.

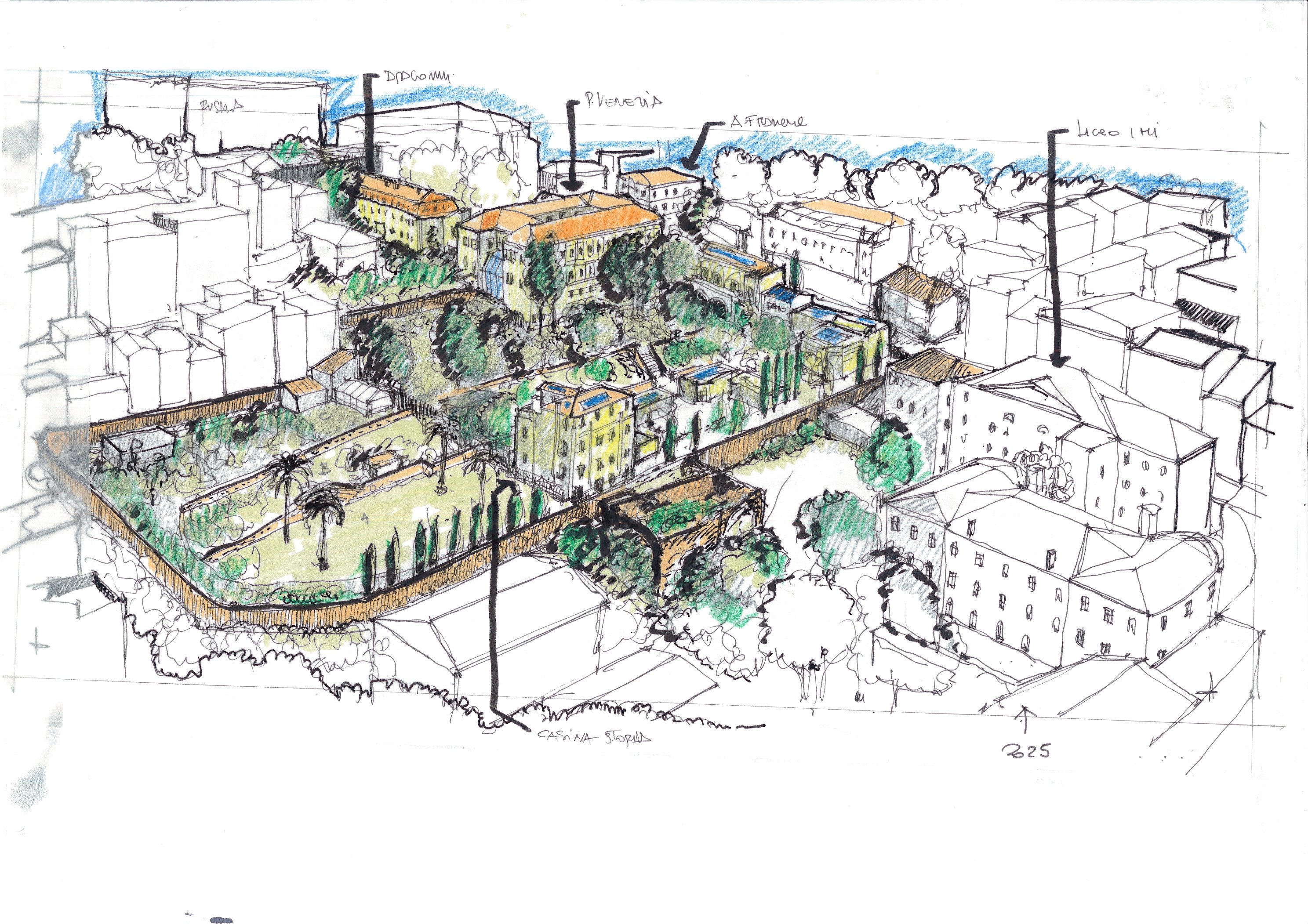

Over centuries, Italian architects, engineers, artists and institutions have left tangible traces in the urban fabric of Turkish cities, particularly in Istanbul and Ankara. These traces are often familiar to the eye but less so to memory. The aim of the project was therefore double: On the one hand, to document and study a significant selection of buildings connected to the Italian presence in Türkiye, focusing specifically on those that still belong to the Italian State; on the other, to reflect on their deeper symbolic meaning as instruments of dialogue, representation and cultural exchange.

From the very beginning of the project, we received the full support of the former Italian Ambassador to Türkiye Giorgio Marrapodi, who immediately understood both the cultural and institutional relevance of this undertaking. His encouragement was not merely formal, but rooted in a clear awareness of the role that architectural heritage plays in strengthening Italy’s presence abroad and in fostering long-term cultural relations. In this sense, the project also aligns with a broader diplomatic vision, in which historical buildings are understood not only as material assets to be preserved but as active tools for promoting dialogue, shared memory and mutual understanding between Italy and Türkiye.

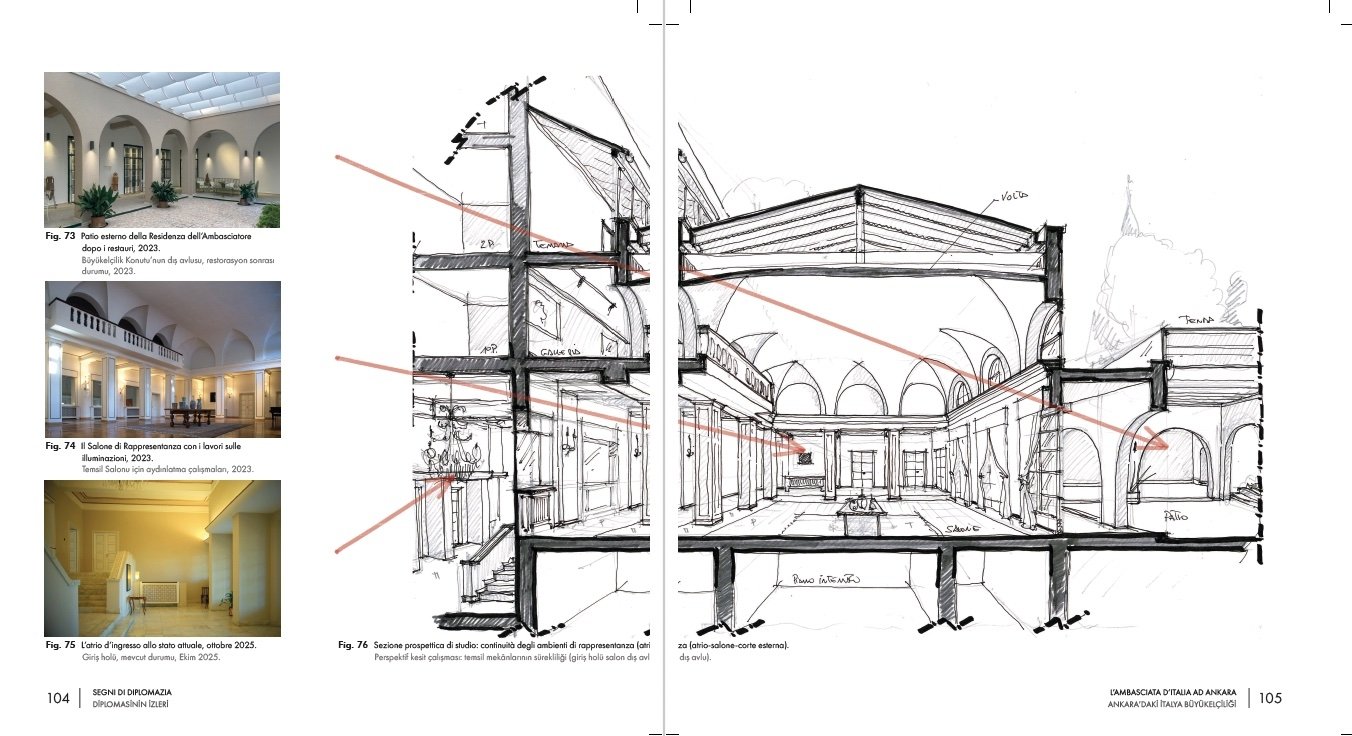

What has been done concretely is not limited to a single restoration site or a single disciplinary approach. The project brought together archival and historical research, architectural survey, technical and sketch representation, restoration studies and critical interpretation. It involved embassies, residences, hospitals, community buildings and former diplomatic headquarters – places that were designed to host institutions, but that over time became part of the everyday life of their cities.

Survey and restoration, in this context, were never understood as purely technical operations. It was conceived as acts of care and responsibility toward a shared heritage. Some interventions were material and concrete, others intellectual and interpretative. Together, they sought to re-establish continuity between past and present, between the original intentions of the buildings and their contemporary role.

This is precisely why the project is meaningful for both Italy and Türkiye. For Italy, these buildings represent a long-standing presence abroad that was not imposed but negotiated through craftsmanship, education and cultural mediation.

Italian architects in the Ottoman Empire and later in the Turkish republic were not only designers. They were also interpreters of modernity, capable of translating European languages into local contexts. Their work abroad reflects an outward-looking Italian culture, deeply rooted in construction, drawing and spatial imagination.

For Türkiye, this heritage is an integral part of its own urban and cultural history. The buildings designed by Italian and Italo-Levantine architects and engineers were absorbed into the life of the city, reshaped by time and made meaningful by local use. They contributed to moments of transformation – from the Tanzimat reforms of the 19th century to the foundation of the republic – when architecture became a key tool for redefining institutions, public life and international presence.

Recognizing, analyzing and restoring these buildings today does not mean celebrating a foreign imprint or a “colonialist” imposition, but rather acknowledging a layered identity shaped through processes of exchange, interaction and mutual influence.

The symbolic value of the project lies precisely in this reciprocity. Architecture here acts as a form of silent diplomacy. Long before official agreements or cultural protocols, buildings were already speaking to one another across borders. An embassy complex in Ankara, a summer residence on the Bosporus, a hospital in Cihangir or a community center in Beyoğlu were all designed to represent Italy, but also to adapt, listen and respond to their surroundings. Their symbolism does not reside only in façades or monumental gestures, but in spatial organization, materials and everyday practices.

Historically, these buildings tell intertwined stories. They speak of reform, modernization, innovation and education, related to diplomacy, care and community life. Architecturally, they embody a hybrid language in which Italian traditions – rational planning, attention to proportion, craftsmanship – merge with Ottoman and Turkish sensibilities, landscapes and climates.

Restoring them today means restoring this dialogue, making visible once again the balance between representation and integration that shaped them. The restored and studied buildings thus acquire renewed significance. They are no longer only witnesses of the past, but active participants in contemporary cultural life. They continue to host diplomatic functions, cultural events, health care services or community activities. Their value lies not only in preservation, but in use. A building that remains alive is also a building that continues to produce meaning, not just a memory from the past.

The book that emerged from this project was conceived as an extension of this philosophy. It is not a simple catalogue of buildings, nor a purely academic publication. Rather, it is a collective narrative that combines essays, historical reconstructions, architectural analyses, drawings, photographic documentation and punctual interventions.

Writing and curating this book was, for me and my colleague Mario, both an intellectual and a personal experience. It required moving constantly between archives and construction sites, between historical distance and physical proximity. There was a strong sense of responsibility: to the buildings themselves, to the people who use them, and to the long chain of architects, patrons and institutions involved. At the same time, there was a deep sense of privilege in being able to give voice to a story that had often remained fragmented or overlooked.

What struck me most during the process was how naturally the project fostered collaboration. Italian and Turkish scholars, architects, institutions and diplomats worked side by side, not as representatives of separate traditions, but as partners in a shared endeavor. The book reflects this plurality of voices and perspectives. It does not impose a single interpretation, but offers a space in which different readings can coexist.

This brings us to the question of support. The project was made possible precisely because it was recognized as a joint cultural initiative. Italian and Turkish institutions provided logistical, institutional and intellectual backing. Diplomatic channels facilitated access to archives and buildings. Cultural institutes and universities supported research activities, while heritage and technical bodies contributed expertise and guidance.

This support was not merely financial or administrative, but it was symbolic. It confirmed that both countries see value in investing in shared memory. From the Italian side, the project aligns with a broader commitment to cultural diplomacy, understood not as promotion, but as exchange. From the Turkish side, it resonates with ongoing efforts to preserve and reinterpret a complex, multicultural urban heritage. The collaboration demonstrated that restoration can be a common language, capable of transcending political or chronological divides.

Ultimately, this project shows that architecture can still play a vital role in international relations, not through spectacle, but through continuity. The buildings studied and restored are modest in some cases, monumental in others, but they all share a capacity to connect people across time and space. They remind us that diplomacy is not only conducted through words and treaties, but also through walls, courtyards, windows and paths. By restoring these architectures and narrating their stories, we are not freezing them in the past. On the contrary, we are allowing them to continue their journey, as places of encounter, memory and everyday life. In doing so, Italy and Türkiye reaffirm a relationship that has been built through the centuries, quite literally, stone by stone.

*Architect and architectural historian, associate professor at Özyeğin University, member of ICOMOS Italy and senior tutor of the Piranesi Prize

Luca Orlandi