© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

The Harvard Gazette has not been alone this year in noting that “The Odyssey is having a moment. Again.” It is right, of course. Last year saw the release of the film "The Return" based upon the Odyssey and another film adaptation, one receiving particular hype due to its being directed by Christopher Nolan and starring Matt Damon, is currently in the making. There have also been new adaptations of the work on stage and in print.

Yet, the “Again” of The Harvard Gazette headline reminds us that the "Odyssey" has never completely lost its hold on the mind of multiple generations of readers since it was first sung by the blind poet Homer on what are now either the Turkish or the Greek shores of the Aegean all the way back in around the eighth century B.C. That it entered into the Babel of stories told by medieval storytellers of different cultures and religions can be seen in the Arabian story of "Sinbad the Sailor" in the "Tales from the "Thousand and One Nights." While this story is certainly not a simple retelling of the tale of Odysseus, it is impossible to deny the influence of the latter on the former.

This is particularly evident from something that happens with Sinbad in his third voyage. His ordeal with a man-eating giant is too remarkably similar to that of Odysseus with the Cyclops Polyphemus to be a coincidence. Not only are members of both trapped crews devoured by their giants on a daily basis, but the means of escape from these monsters is facilitated by blinding their tormentor when it is sleeping, albeit Sinbad’s giant has two eyes rather than Polyphemus’ iconic one.

Then on the following voyage, Sinbad alone avoids the fate of his companions by refusing to partake of a meal set out by a king consisting of suspicious “meats.” By eating of this fateful meal, his companions are rendered beastlike so that they will in turn become such items of repast themselves. This tale resembles the Odyssey both in the eating of the prohibited cattle and sheep of the sun-god Hyperion by all but Odysseus and for which only he escapes full divine punishment and that of the witch Circe, who transforms Odysseus’ companions into pigs.

There are a number of other commonalities between the two characters and their stories, though whether these are the result of Homeric influence on the Arabian tales is impossible to ascertain. These commonalities include both undergoing sea journeys of great life-threatening peril, which involve numerous fantastic creatures. They are also both men of intelligence who use their wits to get themselves out of difficult situations. In addition, they are also both devoted husbands. Less creditably, they share a profound selfishness in which their interests are kept above those of others.

Their dramatic tales have meant that Odysseus and Sinbad are probably the best-known seafarers in literature, yet the story of Sinbad, while well-loved, is seen as lying far below the august heights of the "Odyssey," which along with the "Iliad" also by Homer is one of the two foundational literary texts of Western literature. I cannot claim that the lofty tone of the "Odyssey" is matched by the more picaresque one of the tales of Sinbad, yet I would like to make a case for the character of Sinbad being superior to that of Odysseus. For while Odysseus is the more classically heroic, he is also a far less pleasant and relatable character than Sinbad, which makes the latter deserving of his “moment” too.

To see why Sinbad is comparably the better man, Odysseus himself needs to be looked at in more detail first, and this will involve, in addition obviously to how he appears in the "Odyssey," how he does so in other classical works in which he is a key figure as well, his character being consistent across them. Odysseus is incontrovertibly a hero in the ancient world, a world that, while it has laid so many of the foundation stones of our own, is still more dissimilar to it than we might often think. Some of what ancient eyes would have seen as marks of heroism in Odysseus surely strike modern ones as marks of cruelty. One such example is seen toward the beginning of the "Iliad." In front of all the Greek soldiers at Troy, the character of Thersites makes a speech in which he accuses their commander, Agamemnon, of greed. Odysseus leaps to the defense of the commander without actually countering the core of this seemingly just allegation and threatens to have Thersites, who is weaker than him, flogged naked should he dare presume to speak to his superiors in such a way again. He then strikes him with his staff. Thersites is left humiliated and in pain. To a modern reader, Odysseus here seems nothing more than a bully.

In another instance, there is Odysseus’ treatment of Philoctetes. On the island of Lemnos, on the way to the Trojan War, the foot of this unfortunate Greek archer is injured and due to the resulting stench from the putrefying wound, Odysseus is the one who suggests keeping Philoctetes permanently away from them all by marooning him on the island. Many years later, Odysseus learns that the bow and arrows that Philoctetes possesses are essential for the defeat of Troy. So, Odysseus returns to Lemnos and then tricks Philoctetes into giving them to him while intending to abandon him on the island once again.

Nonetheless, such character failings are submerged under the deluge of blood spilled by Odysseus. For Odysseus, through his stratagem of the Wooden Horse is the one who is primarily responsible for the fall of the city of Troy and the subsequent slaughter and rape visited on his inhabitants.

Then, there is the further mass bloodshed on his eventual return to his homeland of Ithaca. In the long, long absence of Odysseus from his homeland, suitors from Ithaca and the surrounding region have taken up abode in his home, entreating his wife Penelope to accept that her husband is dead and to choose one of them to marry. These suitors spend their days feasting on the produce of Odysseus’ land. Odysseus, upon his return and with the aid of his son, a loyal servant and the goddess Athena, wreaks vengeance on these suitors, slaughtering them all and even one who begs for mercy.

So great is the slaughter that in the aftermath, the suitors are left lying “in heaps, one upon the other.” Yet, Odysseus does not stop here. He also orders the execution of those serving women from his house who had formed attachments with the suitors. Although Odysseus orders them to be dispatched by sword, his son Telemachus instead has them hanged in a row, for what Homer calls a “most piteous death,” poignantly adding that “for a little while their feet kept writhing, but not for long”. In not upbraiding his son for this cruelty, Odysseus implicitly endorses it.

It is not the case that the hands of Sinbad, in contrast, are blood-free. However, the two occasions when he takes the lives of others are exceptional rather than characteristic. At one point, Sinbad is left to die in a cavernous tomb, as he has just lost his wife, the rule in that country being that widows or widowers are buried alive with their dead spouses and a limited food supply. When this food supply runs out, Sinbad, to survive, kills those who are interred alive after him to take their food supplies. The taking of the life of another is generally accepted as legitimate if one is acting in self-defense. While Sinbad’s dire situation here would not qualify, it is akin to that of the "Hunger Games" in which one’s only option is to kill or die.

The second instance in which Sinbad takes a life is after severe provocation. In this case, a strange old man seeks Sinbad’s help in crossing a stream. Sinbad takes him upon his shoulders but once he has brought him across, the old man strangles him with his legs. He then rides Sinbad as a captive animal, allowing him to reach the fruits of the trees. He also regularly defecates on top of Sinbad. “Weeks of abject servitude” pass in this way, until the old man gets drunk and is thrust from Sinbad’s shoulders. With his tormenter lying prone on the ground, Sinbad relates that “I quickly picked up a great stone from among the trees and, falling upon the old fiend with all my strength, crushed his skull to pieces and mingled his flesh with his blood.” I think only a severe moral critic would dare to fault Sinbad for what, with his blood up, he does here.

Most notably, unlike Odysseus, no mass slaughter is ascribed to Sinbad’s name. Moreover, it is not merely in action but also in temperament that Odysseus and Sinbad differ in terms of violence. For Odysseus plans his revenge. He does not act in the heat of the moment, as Sinbad does with his old tormentor. This even applies to the aforementioned serving women. In a particularly disturbing passage in the "Odyssey" that occurs before his revenge, Odysseus is in disguise and bedded down in the entrance hall to his own place. Here, while entertaining himself by “devising evil against the suitors,” Odysseus notices the serving women coming out of the palace and passing by him. They are “laughing and making merry with each other.” The response in the bitter-hearted Odysseus is that “anger swelled up in him and for a while he asked himself if he should leap out then and there and deal death to each of them, or if he should let them lie with the haughty suitors one last time.” He struggles with himself before finally resolving on “patience.”

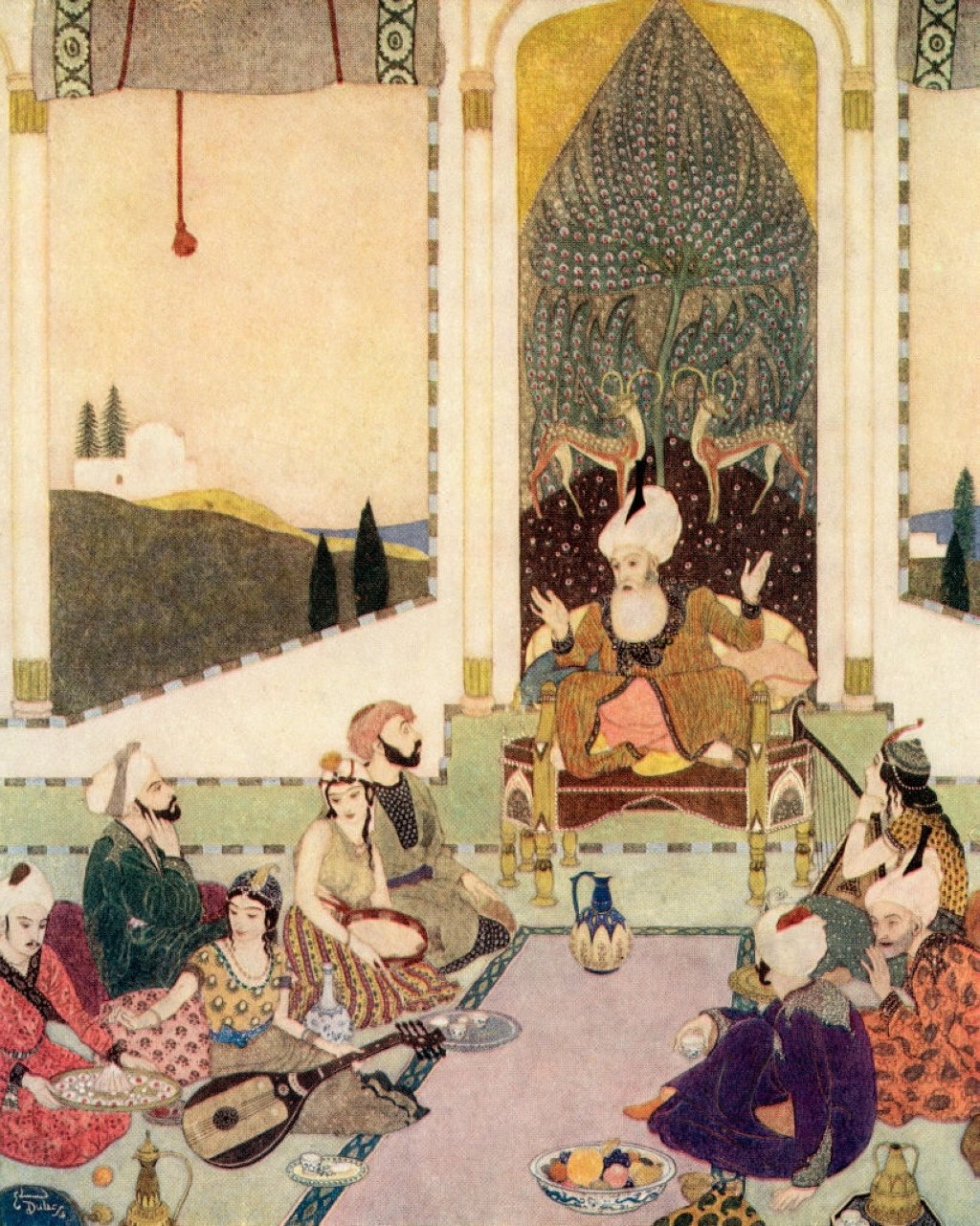

Sinbad, in contrast, is a far less troubled character. The whole tone around him is different, evidenced especially by the joyous feasts that he holds in his Baghdad home. Moreover, even on his travels, when, understandably, his spirit drops in the face of his many trials and tribulations, his fundamental love of life is only temporarily eclipsed. Indeed, in one place, overwhelmed to the point of even considering suicide, Sinbad corrects himself with the thought that “life is very precious.”

Sinbad is also a more compassionate figure than Odysseus, whose cruelty has been amply shown here. This is not only reflected in the warm welcome Sinbad gives to the humble porter of the same name at the beginning of his tales. For upon his return from his sixth voyage, for instance, he “distributed lavish alms among the poor of the city.”

Another great difference between Odysseus and Sinbad that stems from their different characters is the motivation for their travels. Odysseus tries to avoid leaving Ithaca for the war in "Troy" and once he is forced to go to that conflict, he longs to get home. Much of the "Odyssey" is taken up with his journeys across the Mediterranean in pursuit of that goal. Indeed, he gives up an offer of eternal life on an Edenic island in order to do so.

Having on occasion suffered from extreme homesickness myself, I do not feel that Odysseus can or should be faulted for his obsessive desire. Yet, two points about his journey need to be made before contrasting him with Sinbad. The first is that whilst the motivation for it is relatable to us in modern times, its nature is far less so. For in our age of instant communication, the feeling of being absolutely sundered from our loved ones is lost and with high-speed trains and air travel, a return home is no longer an ordeal or “an odyssey.” The second is that Odysseus, whilst he shows an interest in his surroundings, revealed, for instance, by his desire to actually listen to the singing of the dangerously seductive Sirens, in being so focused on his home destination, lacks that simple love of travel that has infected so many wanderers in the world of past times and today.

This is Sinbad’s motivation to travel though, which surely makes him more attractive to us – surely the most highly mobile generation in human history. Sinbad simply has an insatiable appetite to see the new. The riches that Sinbad amasses on his voyages ensure him, upon his return, a life of luxury and idleness should he want it. Yet, Sinbad finds himself bored by such a lifestyle. That he does so is perhaps unsurprising. The 19th-century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer avers that life consists of either boredom or pain. The absence of pain in luxurious living thus simply leaves us in ennui. However, Sinbad is not the pessimist that Schopenhauer is. For Sinbad understands that the latter of Schopenhauer’s two conditions of life is not always a curse. For while trials and tribulations are painful while they are being endured, if they are not of the crushingly traumatic type and if they are overcome, they engender feelings of achievement, which as time passes, create cherished memories of a type that make one feel life has been truly experienced, and produce a desire to make more of them. It is such a motivation that causes many today to suffer the difficulties of taking the unbeaten track, or seek the risks to be found at sea or on the slopes of a mountain.

Hence, the story of Sinbad and his seven voyages is of a man who goes to sea only to suffer disaster upon disaster, but then, upon his return, reframes these ordeals as spurs to action once again. Thus, Sinbad reveals that after his fourth voyage, “the idle and indulgent life which I led after my return soon made me forget the suffering I had endured” and instead he “remembered only the pleasures of adventure and the considerable gains which my travels had earned me, and once again longed to sail new seas and explore new lands.” It is his “thirst for seeing the world” which motivates him, and what is particularly attractive about him is that this continues into old age, with Sinbad confessing that for his seventh and last voyage “though I was now past the prime of life, my untamed spirit rebelled against my declining years and I once again longed to see the world and travel in the lands of men.”

I hope in this piece I have managed to suggest or show that Sinbad, in contrast to Odysseus, is more similar in type to many of us, myself included, making him a more relatable and compelling character than the austere, mean and brutal Odysseus. As such, he surely deserves at least some of the attention currently being lavished on his ancient Greek forebear.