© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

Art history progresses like a student bowing to great ideas. Romanticism drew inspiration from an exalted individualism, while realism and naturalism were inspired by the observational spirit of the social sciences. Traditionally, philosophy leads the way and art interprets it. However, impressionism, which emerged in the last quarter of the 19th century, turned this thousand-year-old hierarchy upside down. It was not a philosophical text or political manifesto, but a painter's observation of a momentary play of light that guided the art, music and literary movements of an entire era.

Impressionists focused not only on what they saw but also on depicting how the eye sees, drawing on fundamental knowledge provided not by artists of the time but by scientists: the science of color.

Artistic freedom through science

The revolutionary power of this new movement was based on scientific color theories developed by figures such as chemist Michel Eugene Chevreul and physiologist Hermann von Helmholtz. In particular, the theory of Simultane Contrast changed painters' palettes forever.

This theory revealed a vital truth involving human psychology: Our eyes tend to exaggerate contrasting colors that are close together. When certain colors are placed side by side, they interact with each other, increasing or decreasing each other's intensity. Until then, artists had mixed colors on their palettes and applied them to the canvas. The work of Chevreul and Helmholtz taught artists to place two colors side by side in their pure form, leaving the mixing process to the viewer's mind. Thus, color ceased to be merely a substance and became a dynamic energy interacting with light.

This scientific basis forced painters to leave the traditional darkness of their studios and work “en plein air,” meaning outdoors. This was because they had to capture momentary changes, the refractions of light at all hours of the day and atmospheric variability. In this process, the unconscious emphasis on light and color in the paintings of William Turner and Camille Corot served as a road map for the impressionists.

Moment in painting, music

The broken brushstrokes and transient atmosphere on the canvas soon formed the basis of music and literature as well.

The most fundamental reflection of this movement in music is undoubtedly the works of Claude Debussy. Debussy's masterpiece, "La Mer," is a quintessential example of impressionism's influence on music. Debussy said he was inspired by a Japanese painting called "Kanagawa Oki Nami Ura" when composing his work. This iconic work separated Debussy from traditional patterns, making him more fluid, meandering and atmospheric, as if the momentary changes in light in a seascape were painted with musical notes. His harmonies and rhythms, like painters breaking down light, transformed sounds into low-resolution, hazy impressions. By using the timbre of sound like the color of light, he removed music from being a rigid structure and transformed it into an emotional impression.

Similarly, in literature, writers moved away from rigid descriptions of external reality, turning instead to subjective impressions, the inner worlds of characters and the “stream of consciousness” technique. Thus, instead of a philosophical text, a work of art became the new aesthetic compass of the entire cultural world.

This scientific and technical revolution also brought about a mental liberation. Unlike centuries of artistic oppression – sometimes the Church's imposition of religious grandeur, sometimes the glorification of war, sometimes the imposition of political or communist ideas – impressionism freed the artist from these coercive subjects.

The subject of the painting was no longer a heroic tale, a mythological fantasy or a moral lesson; the subject was the moment itself. The pursuit was of that single, unique second when the eye perceives a landscape or a person – a moment that would never return in the same way. The painter realized that he could work on the impression of a wheat field at sunrise and the impression at noon, even on the same subject thousands of times. Each work would be different because the light was constantly changing, and the atmosphere was constantly flowing.

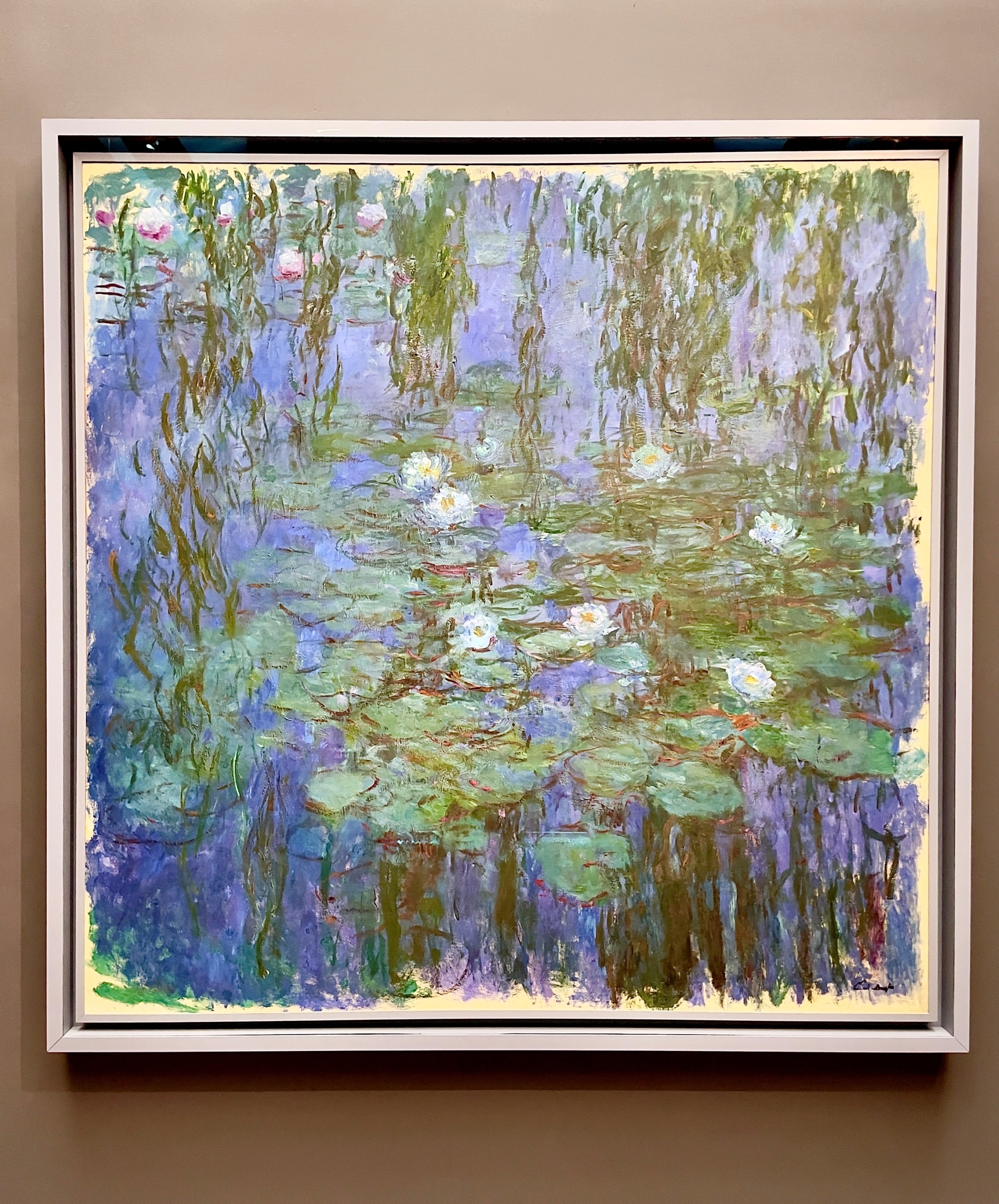

This was not just a liberation from within Western art. Claude Monet, the artist behind impression, Soleil Levant – the namesake of impressionism – was also fascinated by Japanese art. He was particularly influenced by prints of Ukiyo-e. The artists of this movement, led by Monet, were deeply influenced by Eastern philosophy and Japanese culture, and this left an impact on their whole lives. Inspired by nature, Monet created a Japanese garden at his home in Giverny. He transformed the existing pond into an Asian-inspired water garden and added a Japanese-style wooden bridge to it. This led to the creation of his series of paintings depicting water lilies, which he painted repeatedly. Monet stated, “Perhaps I owe my being a painter to flowers; the richness I have achieved comes from nature, my source of inspiration,” expressing how he reshaped the West's aesthetic perception with the Japanese's simple, momentary and dynamic compositions.

Spirituality, continuous creation

It is precisely at this point that I believe the impressionist quest to capture “the moment” coincides with the Sufi belief in continuous creation. The 29th verse of Surah al-Rahman states, “Every day He is engaged in some work,” meaning “There is a universe that is constantly being created, constantly being renewed, without any interruption.”

According to the impressionists, the external world is in a state of constant change and transformation. Our view of the world is constantly changing and renewing itself. Here we can see a deep parallel with Islamic thought. In Islam, the universe is not conceived as a fixed and static entity, but as one in constant change and renewal. The concept of continuous creation conveys that Allah's act of creation is instantaneous and ongoing.

Impressionist artists, on the other hand, focus on “a single, unique moment that can never be recaptured” and express this spiritual reality aesthetically. Monet, while painting the same water lily or the same cathedral over and over again, tries to show that every moment is unique and transient. This perspective reveals that the universe is not a static photograph but a continuously flowing film.

This approach emphasizes Allah's infinite power and the continuity of his creativity. If a moment can never be repeated in exactly the same way, it means that creation is renewed every second. By transferring the momentary impression onto the canvas, the painter observes divine manifestation and glorifies change itself.

All the abstract forms, experiments that break traditional rules and free brushwork we encounter today when visiting modern and contemporary art galleries owe their foundation to the challenging struggle of the impressionists. They were sometimes ridiculed, sometimes rejected from the Paris Salon exhibitions, which were very important in France at the time, and sometimes heavily criticized by academic circles and critics. They were ridiculed in their first exhibitions, described as “unfinished” and “crude.”

These artists stood against the academic hierarchy of subjects and opened the door to subjectivity in art, guided by scientific knowledge. If they had not freed themselves from the pressure of the Church, the Academy and politics and pursued only the moment, radical movements such as fauvism, cubism and abstract expressionism would never have emerged. This difficult struggle for the existence of impressionism is the cornerstone of today's modern and contemporary art.