© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

Twenty-five years ago, Ozan Baran landed in the United States with $600 in his pocket. Today, he runs a company valued at around $500 million, connecting truckers and shippers through a digital platform he calls the "Uber of trucking."

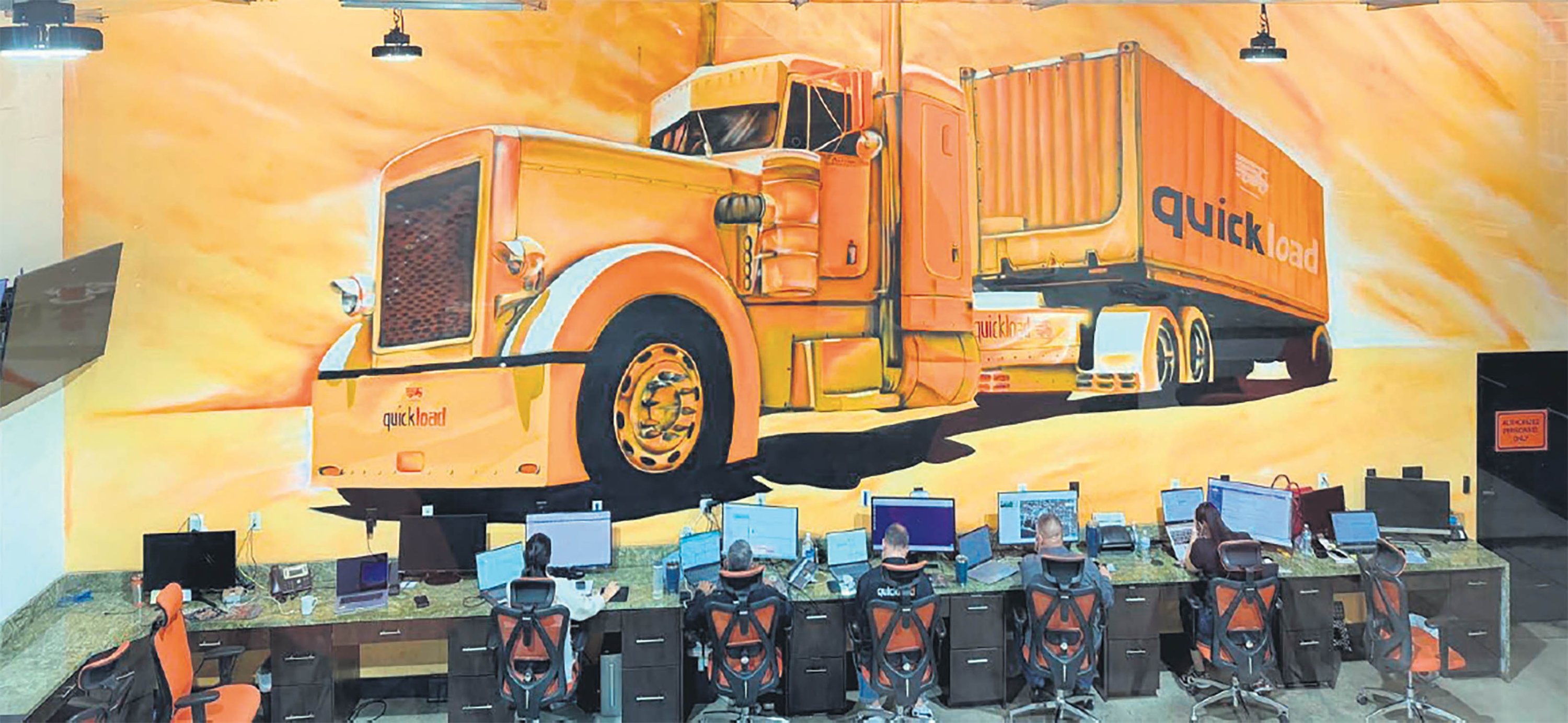

Baran is the founder and chief executive of Quickload, a Miami-based logistics technology company that doesn't own a single truck. Instead, it operates as a platform linking trucking companies with businesses that need goods delivered, a network that now spans all 50 U.S. states and serves almost 3,000 transport firms.

Everything from marble and gas to steel structures and small parcels can be transported through the system, according to Baran.

Baran's journey began in 1999, when he arrived in the U.S. after graduating from university. By 2005, after several odd jobs, he had saved $10,000 before stepping into logistics and buying a $60,000 truck. That vehicle bore a personalized plate: TC 001, a nod to his Turkish roots.

"For years, this plate traveled all over the U.S.," he recalled. Then new vehicles joined the fleet, before the company eventually entered a new phase in logistics to connect customers in need of vehicles with trucks it didn't own through an app.

Quickload's system helps trucks that drop off their loads find jobs on their return trips, reducing "empty miles" – the distance trucks travel without cargo – which Baran says is saving fuel and has earned praise in the U.S. for its environmental impact.

In essence, the company filled a gap in the market, Baran says.

Customers use the app to specify the shipment details, including where it will be picked up and dropped off, whether storage is needed, and then choose the most suitable option among various alternatives.

"This allows them to minimize costs," Baran noted.

Developing the software and infrastructure took three years. Quickload launched operations in early 2017, and within a year, it had drawn attention across the U.S. logistics industry. In 2018, Baran was honored with the Best Businessman Award at Miami Synchronicity, a recognition given to emerging entrepreneurs in the region.

Although Quickload's headquarters remain in Miami, the company's software operations have been moved to Türkiye, where Baran says a team of 75 young engineers maintains and develops the platform.

"We're very good at this field," Baran said. "As a nation, we are practical thinkers, which makes us skilled at generating solutions. We can do with four people what might take 20 elsewhere."

Quickload's executive team also includes several Turks. Beyond the tech team in Türkiye, the company operates a 200-person call center in Colombia.

Baran is among a growing group of Turkish entrepreneurs establishing a foothold in the United States.

Last month, he attended a dinner in New York on the sidelines of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's visit to address the United Nations General Assembly, where Turkish businesspeople based in America discussed expanding bilateral trade.

The meeting underscored the importance of removing barriers to trade and increasing investment, Baran said. "President Erdoğan emphasized the role of businesspeople," he added.

Not content to stop with logistics, Baran has also launched a new tech venture, a virtual office platform called Parea.

The application recreates an office space in three dimensions, allowing employees working remotely to see where colleagues are "virtually," what they are working on and to communicate in real time.

Parea strengthens the remote work model that became essential after the pandemic. Baran notes that the app, which operates on a monthly subscription model, has attracted interest from companies in both the Turkish and U.S. markets.

"Even if there's an ocean between you, Parea lets you instantly follow the outcomes of an office meeting," he noted. "This app eliminates distances in business life, making work easier for white-collar professionals."