© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

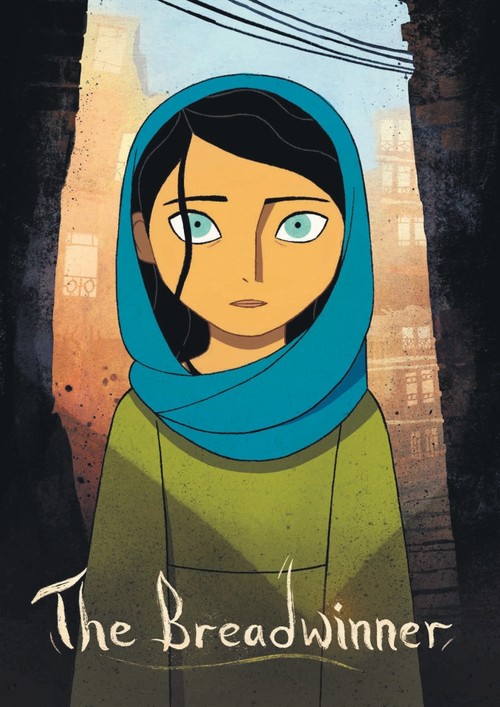

The fifth edition of the Ajyal Youth Film Festival in Doha opened with the animated film "The Breadwinner," telling the story of an Afghan girl, Parvana, who decides to dress like a boy to be able to go to the market unharassed by the Taliban. Just hearing the name Kabul, like hearing the name of many other (once) beautiful towns in the Islamic world, is enough to make one feel a pang in the heart. Set in Kabul, "The Breadwinner," as you knew it would, holds your feelings hostage for its duration, because you know the sad story it is telling is true. Director Nora Twomey has chosen a palette of very deep reds, oranges and blues, which lift the spirits a little and carries you through. To allow breathing space for the audience and a counterweight to the sorrows of the present, the script is written in a way that allows us to see a more colorful, parallel fairy tale world that Parvana narrates to her brother and her friend.

The film opens with Parvana trying to sell a very bright red dress with little mirrors on it. She is sitting next to her dad in a market in Kabul, and he quizzes her about the history lessons he has been giving her about Afghanistan. He asks her about the Silk Road, and as she tries to remember her lessons, she looks around the dusty market, with bombed-out buildings in the background. She repeats the name Silk Road in frustration and then hurls herself toward the dusty ground - there is certainly nothing there to remind her of the riches that once went through the city of Kabul. The colors, smells and textures of the Silk Road are long gone, and they remain only in her father's stories and in glimpses here and there in Parvana's mother's kitchen and a bonbon factory that she manages to rummage through with a friend later in the film.

Twomey's film reminds us that the Silk Road, like Kabul, has been robbed of its meaning and focuses on the tradition of storytelling as a means to keep the memory of the very meanings of words. When Parvana's father starts retelling her "lesson," about the various empires and emperors that fought in and shaped Afghanistan, the film goes into brighter colors, and the conventional animation texture turns into the texture of a miniature-style pop-up story book: This is how Twomey has chosen to differentiate the registers of her own storytelling. The aesthetics of the figures are very reminiscent of Marjane Satrapi's "Persepolis," though of course, hers was in black-and-white, and the historical figures depicted in Parvana's father's "pop-up" book are similar. Parvana's father tells her of the "official" history, and she, in turn, tells a fairy tale to her toddler brother Zaki to keep him occupied when he is afraid or hungry. Parvana's fairy tale starts with a feast at a village with sumptuous food, and mirrors the stories of the '70s that her father tells as part of the history of Afghanistan. Right about the time when he reaches Taliban rule and the imposition of the burqa in his history lesson, he is threatened by the Taliban and then finally taken to prison for bringing his daughter to the market.

With her father gone, the storytelling gradually turns into a way Parvana soothes herself in her moments of crises and a way through which she tries to make sense of her older brother's death, which we learn has happened some time ago. The older brother, Suleyman, haunts her story, with his clothes that she wears to pass as a boy, and with his absence as the rightful breadwinner for the family. In that way the film turns into a story about stories and has rightly been, along with a Qatari short film "1001 Days," one of the inspirations for the festival's trailer with the beautiful animated falcon and two children it is flying on its back: "Some sorrows can change a human being, but story telling can rescue the heart." The organizers of the festival have repeated the sentiment on several occasions, saying how important it is for them to be sharing stories with people at a time when their country seems to be isolated from its neighbors.

When Parvana tells her fairy tale to her friend Dilaver, the impatient Dilaver asks, "Is it a happy story or a sad story?" echoing the very question that went through my mind when I first saw the poster for the film. And when Parvana tells Dilaver, "Wait and see!" I feel as reprimanded as Dilaver does -- even if we fear that "The Breadwinner" might not end happily, we still have to listen to this story from Kabul, wait and see what happens to the characters in the end. The film also emphasizes the collective nature of storytelling: When Parvana takes her time telling it, Dilaver introduces a character into Parvana's tale, and although Parvana objects at first, she quickly embraces it and makes it an important clog in her plot.

It is only when Parvana, now named Atash (for a Turkish viewer it is a delight to understand Afghan words and the references Parvana to Atash, "moth" to "fire"), returns to the market to sell the red dress and a couple of other of her family's belongings that might be of value that I register what she is calling out as she is selling her things: "Anything written, anything read!" Because the dress is so red, I concentrated on the word "red," as if selling anything that has the color red can be a trade in itself. A very big man asks her where the man who usually sits there is. Fearing to draw attention to herself, Parvana/Atash says he has gone on a trip, and so the man asks Parvana to read a letter he has received. The way the big man slumps on one arm when he hears that his Hala (the man explains that Hala means the halo that appears around the moon, a name the Turkish audience will already have understood when the film is hopefully shown in Turkish cinemas) has passed away is so true to life that you feel with him. The way the man's body crumbles into itself, implodes, is one of the finer moments in the film where Twomey has captured the different shades of grief.

This is an important moment because throughout the film we have seen men dressed like him as members of the Taliban, causing terror throughout Kabul. Yes, the Taliban are many and ferocious in the film, and when toward the end of the story we see American jets tear the Kabul sky, Twomey is careful not to portray this as "liberation," but as the continuation of the horrors that the Afghans have to go through. The only catharsis the bombs and the coming conflict offer is when we see the young member of Taliban who has been hounding Parvana and her family from the beginning of the film is taken on a Toyota truck to go fight the Americans. We may pause to wonder what turned this young man into the revengeful and life-hating monster that he is, but there is still some poetic justice in the fact that he will now come face-to-face with the violence that he seems to have been yearning for.

"The Breadwinner" is there precisely to turn attention away from the Taliban to the people of Kabul whose spirit will see the troubles through. As another line in the film says, "Stories remain with us when all else is gone."