© Turkuvaz Haberleşme ve Yayıncılık 2026

Zohran Mamdani’s historic victory in New York’s mayoral primary is more than a political upset. It’s a moment of symbolic rupture and renewal for Muslim communities long marginalized in the American urban imagination. For the first time, a Muslim candidate has not only gained visibility but claimed the right to govern one of the world’s most complex, diverse and influential cities. In doing so, Mamdani reframes what it means to be Muslim, progressive and urban in 21st-century America. His rise invites a deeper question: What does it mean for Muslims not merely to live in cities in a country like the U.S., but to lead them?

Mamdani’s surprise win over former Governor Andrew Cuomo was more than a generational upset; it was a direct challenge to the Democratic establishment. While Cuomo’s campaign was built on experience and name recognition, Mamdani’s appeal stemmed from authenticity, grassroots energy and a rejection of politics-as-usual. His victory reflects a growing divide in the Democratic Party between institutional centrism and insurgent progressivism. For many New Yorkers, Mamdani represents a post-Trump era Democrat; one who does not retreat into moderation, but who sees the city itself as a site of ideological struggle. In that sense, his campaign echoed international movements for the “right to the city,” a call to reimagine urban space not as a commodity, but as a common good. His win asks whether urban governance in the 21st century can finally center people over profit.

Mamdani’s campaign centered on one of New York City’s most urgent crises: affordability. In a city where a one-bedroom apartment can exceed $4,000 a month, he proposed a rent freeze, universal child care, free bus service and expanded public housing. But beyond policy points, what made Mamdani distinct was how he reframed urban justice, not as a technical issue, but as a moral one. He named housing, transportation and child care not just as services, but as rights. He addressed not only economic exclusion but also cultural alienation, advocating for a city “where everyone belongs.” His campaign headquarters in Queens, staffed by working-class volunteers and filled with multilingual signage, embodied the pluralism he preached. In this sense, Mamdani didn’t just run for office, he reimagined what a mayoral campaign could look like in a city of immigrants, renters and strugglers.

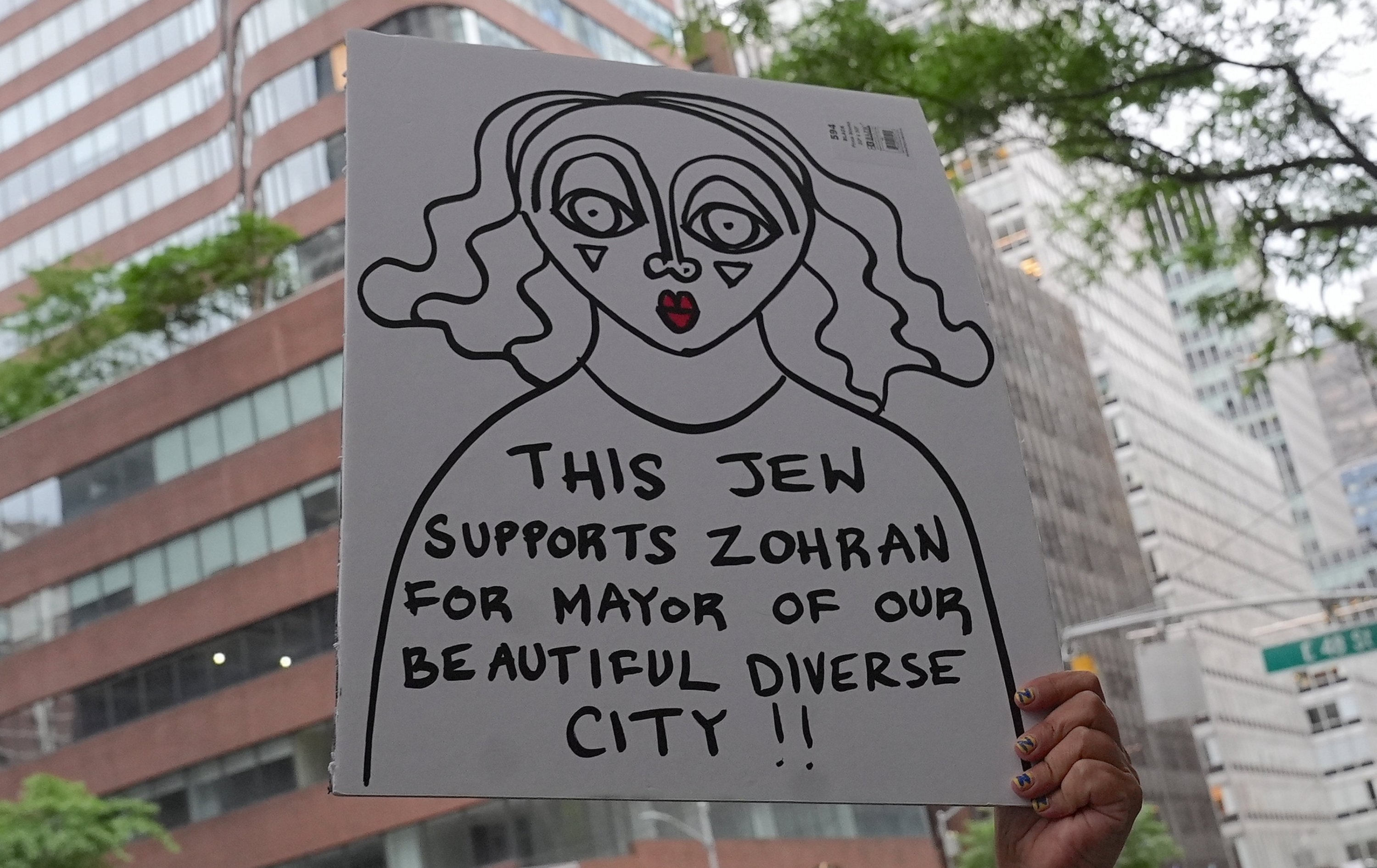

For decades, American cities have celebrated diversity while keeping some communities, especially urban Muslims, largely invisible. Present in daily life yet absent from media and policy, their mosques stood on side streets, their stories excluded from the civic imagination. Mamdani’s rise disrupted this erasure. His campaign didn’t just seek inclusion, it claimed political, architectural and emotional space for Muslims as co-authors of urban futures.

Mamdani’s victory resonates with a generation of urban Muslims, young people who have come of age in America’s dense cityscapes while balancing mosque, subway, protest and poetry. These are not just Muslims in cities, but Muslims shaped by cities: by their contradictions, their solidarities and their injustices. In boroughs like Queens and the Bronx, where halal food trucks park next to eviction notices and Friday prayers echo near gentrifying neighborhoods, Mamdani’s campaign felt personal. It offered a new kind of visibility, not only as Muslims, but as renters, workers, artists and neighbors. His politics reclaim urban belonging from surveillance and suspicion, grounding it instead in care, affordability and democratic voice. For urban Muslims, this was not just a political win; it was a moment of collective authorship.

At the heart of Mamdani’s campaign was a vision of an “affordable city,” a city not only for the rich or the tech elite, but for the janitor, the Uber driver, the immigrant mother with three kids in a one-bedroom apartment. For many urban Muslims, affordability is not an abstract economic term; it defines the quality of their faith, family and future. Rent freezes, free public day care and universal transit access were not just policy items; they were answers to Friday khutbahs about justice, to mothers’ whispered prayers about school fees, and to late-night conversations among roommates about staying or leaving New York. Mamdani spoke in a language that linked policy with dignity. His promises echoed the spiritual and material anxieties of a generation negotiating both prayer rugs and parking tickets, both home and exile.

Mamdani’s candidacy was more than a political contest; it became a vessel for collective imagination. In a city fragmented by inequality and cultural segmentation, his campaign coalesced scattered frustrations into a shared “we.” Among urban Muslims, this meant more than religious representation; it signaled the possibility of being seen as full civic actors without apology or assimilation. Mamdani did not merely mirror existing demands; he assembled them. In neighborhoods where halal carts and mosques coexist with housing insecurity and police overreach, his name became shorthand for the hope that visibility could translate into agency. His victory was not just electoral, it was hegemonic, in the sense that it redefined who the city is for, and who gets to shape its story.

Mamdani’s rise has unsettled the political grammar of New York. In contrast to the law-and-order, market-first urbanism associated with figures like New York City Mayor Eric Adams or President Donald Trump’s derisive labeling of cities as “trash heaps,” Mamdani offered a counter-narrative: the city as a site of care, dignity and redistribution. His platform was not just a policy package but a moral vision of urban justice. By articulating the frustrations of marginalized communities, particularly immigrant Muslims, he challenged the dominant framing of who cities are meant to serve. In doing so, he reframed urban identity not as a battleground of control, but as a commons of shared futures.

In the wake of Mamdani’s victory, the question is no longer whether Muslims belong in the urban story, but how they will shape its next chapters. His rise challenges cities to become not just spaces of coexistence but arenas of justice, voice, and shared authorship. As urban Muslims across the U.S. look to New York, they see not just a win, but a beginning. The city, long a place of arrival, may now become a place of transformation.